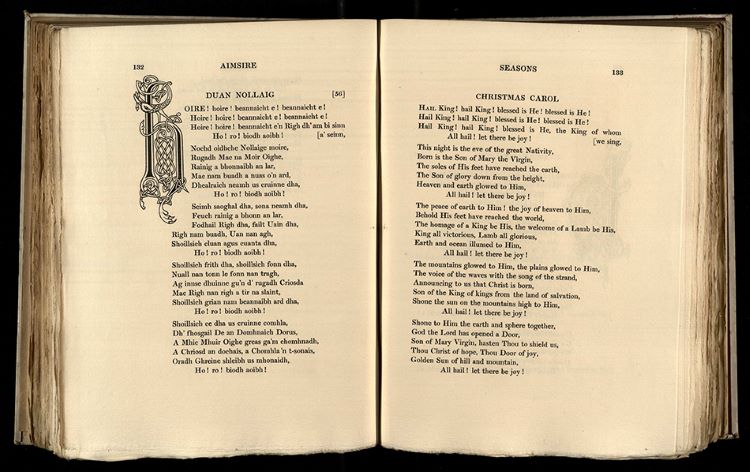

Image: from University of St Andrews Special Collection, first edition of “Carmina Gadelica” vol.1 (Edinburgh, T & A Constable, 1900), Christmas song with Alexander Carmichael’s English translation

Alexander Carmichael (1832–1912) was, like Robert Burns, an exciseman; like Burns, he was fascinated by the traditional music and stories of his native Scotland. However, while Burns’s creative work is still (mostly) celebrated as a milestone contribution to the curation of Scottish song traditions, Carmichael’s fieldwork had a much less positive critical legacy through much of the twentieth century. Recent work by Domhnall Uilleam Stiùbhart of Sabhal Mòr Ostaig, University of the Highlands and Islands, suggests that it is time for a twenty-first century reappraisal of both the man and his work.

Carmichael was from the Isle of Lismore in the Gaelic-speaking West, but he lived and worked for much of his adult life in Uist in the Outer Hebrides. After his death his folkloric work fell into critical disapprobation—as did much anthropological research from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries—because his evident tweaks, edits, and even occasional additions to the material he recorded; and also because of apparent gaps in his field notes. For some scholars at least, Carmichael’s work seemed to be an unreflective imperial-age Anglophone appropriation of songs and stories from Gaelic Scotland. Ideologically, Carmichael’s brand of ‘Celtic twilight’ nationalism hasn’t aged well. However, Dr Stiùbhart’s work with the surviving papers suggests that much can still be learned from Carmichael’s work. In particular, the tension between the textual biases of Scottish Presbyterian culture, and the perhaps more oral approaches of the Catholic culture of the Outer Hebrides, is of continuing interest, as new historiographical approaches encourage us to think productively about what happens in zones of dynamic cultural interaction. The nineteenth century was a period when Gaelic culture in general seemed to be under threat from clearance and emigration; Stiùbhart’s work, however, has suggested that in some respects these upheavals may in fact have prompted and intensified the use of and urge to preserve song, hymns, and charms from within as well as from outside the Gaelic communities. Attention to the field notebooks used by Carmichael also makes it clear that women played a vital role in the cultural transmission and survival of many oral practices, from birth to funerary soundscapes.

Carmina Gadelica—roughly translated, Gaelic Poems or Charms—is a six-volume anthology of sacred and secular songs mainly collected from the Western Isles. Carmichael was directly responsible for volumes 1 and 2; his notes were edited into two further posthumous volumes; while two final volumes were based on more modern research incorporating additions from later editors, in particular Angus Matheson, a native of North Uist, Professor of Celtic Languages and Literature of the University of Glasgow. The early volumes consist of hymns, prayers, and charms, spiritual material broadly Catholic in nature reflecting the needs of a rural population, for example in protecting cattle or ensuring safety in childbirth. Carmina Gadelica was primarily a literary curation of folk religion.

Stiùbhart’s research on Alexander Carmichael and Carmina Gadelica includes the following topics:

- Ritual lament or ‘keening’ at Highland funerals. The soundscape of death is a fascinating anthropological topic. Women could make themselves and their concerns heard at key moments while commemorating and bewailing the dead—although later Presbyterian practice restricted graveyard attendance to men.

- The distinctive nature of Catholic folk religion in the Scottish Highlands. Research into Carmina Gadelica suggests that Carmichael’s vision for his multi-volume compendium reflects contemporary Celtic nationalist perspectives on the Protestant Reformation as being a culturally disruptive outside imposition threatening older, more indigenous Catholic oral traditions, customs, and beliefs.

- Attention to Carmichael’s field notebooks suggests that while Gaelic culture was already under pressure in the nineteenth century, this may have meant that belief and practice in charms and other folk magic even have increased during the period.

- Edited and introduced the collection Alexander Carmichael: Life and Legacy (Islands Book Trust, 2008)

Domhnall Uillearn Stiùbhart is a folklorist rather than a ‘musicologist’. However, his work on sound is musically sensitive and very useful. Musicologists need to think, perhaps, less prescriptively about what constitutes ‘music’ in these contexts. Is a charm a song, or an act of magic? It’s surely both. Thinking a little less nervously about the curation of musical ‘objects’, and more about the anthropology and practice of sound-making, brings this material sharply back into focus as a useful resource.

Further Reading

By Domhnall Uillearn Stiùbhart:

- ‘Keening in the Scottish Gàidhealteacht’, in P. Jupp and H. Granger (eds), Death in Scotland: Chapters from the Twelfth century to the Twenty-First (Peter Lang, 2019), pp. 127–146.

- ‘The theology of Carmina Gadelica’, in D. Fergusson and M. W. Elliot (eds), The History of Scottish Theology Volume 3: The Long Twentieth Century (Oxford University Press, 2019), pp. 1–19.

- ‘Leisure and recreation in an Age of Clearance: The case of the Hebridean Michaelmas’, in J. Borsje, S. Mac Mathúna, A. Dooley and Toner (eds) Celtic Cosmology: Perspectives from Ireland and Scotland (Papers in Mediaeval Studies 26, PIMS Publications, 2014), pp. 246–306.

- ‘The making of a charm collector: Alexander Carmichael in the Outer Hebrides, 1864 to 1882’, in J. Kapolo and W. Ryan (eds), The Power of Words: Studies on Charms and Charming in Europe (University of Pecs, 2013), 25–66.

On the Carmina Gadelica and Alexander Carmichael generally:

- Carmina Gadelica: Hymns and Incantations, with Illustrative Notes on Words, Rites and Customs, Dying and Obsolete, Orally Collected in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland and Translated into English, by Alexander Carmichael (6 vols, Oliver and Boyd, 1900–1971).

- Esther De Waal (ed.), The Celtic Vision, from the Carmina Gadelica (Longman & Todd, 1988).

- Noel Dermot O’Donoghue, The Mountain behind the Mountain: Aspects of the Celtic Tradition (T & T Clark, 1993).

- Laurie Patton, ‘Alexander Carmichael, ‘Carmina Gadelica’, and the nature of ethnographic representation’, in Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium, 8 (1988), 58–84: an early call for reappraisal of Carmichael’s work, while at the same time listing the many reasons why anthropologists were suspicious of the work.