Soundyngs features in this post research by Dr Nina Baker, independent engineering historian, on the unexpected connections between the great Scottish engineer James Watt and 18th century musical instrument building, including organ building, in Glasgow. For anyone curious about the ingenious links between the industrial revolution and organology, read on…

- Featured image: Sculpture of James Watt on Glasgow Athenaeum building (author’s photo)

On the 28th June 1918, with the First World War still raging in Europe, the Lord Provost of Glasgow announced the acceptance of the gift to the city of a small chamber organ. George W. Macfarlane, the donor, had just paid £400 for it at an auction. The organ, with its pipework hidden behind a frontage of false, gilded pipes, was of a size suitable for use in a living room or small hall, rather than a church. This was the organ known then, and now, as the ‘James Watt Organ’, and which remains in the city’s museum collection.

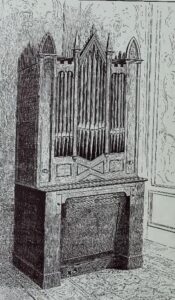

Image 1: ‘James Watt organ’ from Forbes, Peter, ‘James Watt’s Organ’, The Regality Club second series, part 1 (Maclehose, 1889), pp13-19

Whenever this organ has been displayed over the years, it has attracted public interest and the revival of a controversy going back to the 1880s, as to its true provenance and history. Most writers about Watt make at least some mention of this organ, some getting well into the whole religious controversy of the period, relating to the use of organs in churches (see Payzant, 1953, and Mitchell, 1905).

It is called the ‘James Watt Organ’ because it has generally been believed to have been made by James Watt in Glasgow in the 1760s. At that period, early in Watt’s career and before his great invention of the separate steam condenser, he augmented his income by making and selling musical as well as scientific instruments (see Smiles, 1865, p.100).

Image 2: Display of musical instrument components from James Watt’s workshop on display at London Science Museum (author’s photo)

Before its donation to the city, its previous owner was a wealthy collector, Adam Sim, who put onto the organ a silver plate with his (unauthorised) family shield when he bought it in 1863. This plate states that the organ was made by Watt in 1762, which was what Sim understood from a deathbed statement by an even earlier owner, Archibald Maclellan. However, the scarcity of records from Watt’s own time means that neither the most detailed archival research of Watt’s papers (Hills, 2002, and Reid & Gillen, 2013), nor the most careful examination by Glasgow organ conservation expert, Michael Macdonald (Wright, 2002), have been able to definitely connect this organ with organs Watt is known to have made.

Watt was much admired in his own lifetime, so there was the understandable desire by people of all levels of society to find tangible connections with the great man. Even now, we really want to think that this object or that was his property or was actually made by his own hands. The organ has also, wrongly, been associated (Thomson, 1905, p.26) with an organ played in a single service at St Andrews in the Square church, Glasgow, in 1807, when musical instruments were not permitted by the Presbyterian Church of Scotland. There is no link between the ‘James Watt Organ’ and the instrument involved in that scandal, despite claims repeated from time to time.

Evidence that the organ owned by Glasgow City Council’s Museum Service is likely to have been made by Watt falls into two groups: written documents from Watt’s time and the features of the organ itself.

Watt’s accounts books mention payments for making a barrel organ (Dickenson & Jenkins, 1927, p.18) for his friend, Dr Black, and a finger organ for a lodge of freemasons (ibid, p.11). These also mention Watt making a small organ for himself, which was described as having the appearance of a table, but which hid an organ within. Biographies of Watt claim that he would startle visitors by activating a hidden movement in the ‘table’, such that music was produced (Muirhead, 1859, pp.48-49). Thus, presumably, this ‘table’ organ must have been a barrel organ operated by a clockwork mechanism, whereas the ‘James Watt Organ’ is bellows-operated.

The ‘James Watt Organ’ was built with keyboards and vertical pipes and has three stops, described by Michael Macdonald in his renovation report for Glasgow Museums as follows:

“There are three drawstops controlling the Stopped Diapason 8ft, Flute 4ft and Fifteenth 2ft. Originally there was a fourth stop that was controlled by a foot pedal which appears to have been a small scaled reed stop (Regal) which started at fiddle G.

There are spaces for another three pedals, one of which still has most of the mechanism to control a shifting action on the 4ft & 2ft due to a double table-top and slides. The next pedal should have been the foot pedal for pumping the wind into the bellows. No mechanism other than a metal trundle survives on the final pedal, which could have worked a transposing keyboard.”

(Macdonald, 2018)

Its various innovative features include a transposing keyboard which could automatically change from one musical key to another, and some parts normally made of wood but in this case made of metal. These are indications that Watt did in fact build it since these innovations did not appear in other organs during his lifetime.

It seems likely but not absolutely certain that Watt made the organ in the Glasgow Museums’ collection, in order to practice organ-building and to experiment with innovations. There were no books on organ building until 1800, but he could have consulted books on the science of music and tuning of organs, and even possibly have taken apart other older instruments to understand their mechanisms. This particular organ was left behind in his old shop in Glasgow when he moved to Birmingham to take up his partnership with Matthew Boulton, and then passed through several owners’ hands before being given to the city. Whilst its provenance will probably never be definitively proven, the balance of likelihood is that it was indeed made by the great man.

Further Reading

- Baker, Nina, ‘James Watt as Musical Organ Maker: Myth or Reality?’, in Caroline Archer-Parré, and Malcolm Dick (eds), James Watt (1736-1819): Culture, Innovation and Enlightenment (Liverpool, 2020; Liverpool Scholarship Online, 2020), 209-229

- Dickenson, H. W. and Jenkins, R., James Watt and the steam engine (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1927), accessed 25 August 2018

- Hills, R. L., James Watt: Volume 1: his time in Scotland, 1736-1774 (Ashbourne: Landmark Publishing Ltd, 2002)

- Macdonald, Michael, The James Watt Organ (2017). Blog based on his 2014 conservation report for the Glasgow Museums’ Service and the Leche Trust, which financed the project. (accessed 29 March 2018; Tumblr sign-in required)

- Mitchell, J. O., ‘Some old Glasgow organs’, in Old Glasgow Essays (Glasgow: Maclehose & Son, 1905), 45-62, reprinted from Glasgow Herald, 23 March 1889

- Muirhead, J. P. , The Life of James Watt (London: John Murray, 1859)

- Payzant, G. B., ‘Organ controversy in Scotland’, Dalhousie Review, 32(4) (1953), 44-48

- Reid, J and Gillen, G., ‘The Watt organ: Its origins and ownership’, The Ashlar, 51, (Dec 2013) ISSN 1471-7743 and an unpublished report by G. Gillen for Glasgow Museums Service on which the Ashlar article was based.

- Smiles, S., Lives of Boulton and Watt (London: John Murray, 1865)

- Thomson, J. A, History of St Andrew’s Parish Church (Glasgow: R Anderson, 1905)

- Wright, Michael, ‘James Watt: Musical Instrument Maker’, The Galpin Society Journal, 55 (Apr. 2002), 104-129

Author Profile: Dr Nina Baker, OBE, DL, PhD, BSc, FIES, HonMWES

After an early career as a Merchant Navy deck officer, Nina Baker’s doctoral research was in engineering, and she has lectured on materials science and worked as a university engineering research administrator. She has a particular interest in the history of women in engineering. Profiled in the “Women Also Know History” site here and her own Women Engineers blog.