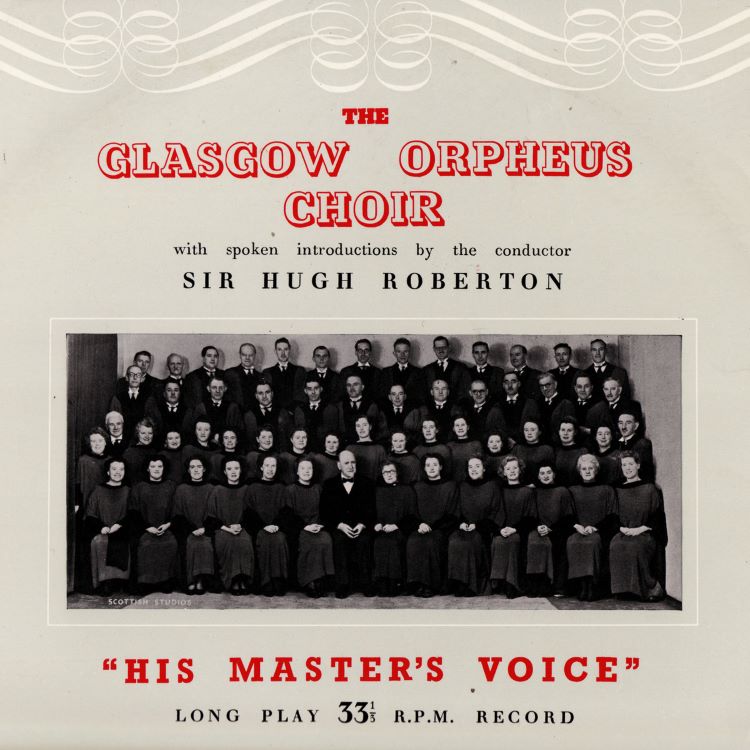

Image: Glasgow Orpheus Choir v1, recorded in the early 1950s as a heritage album

A few years ago, preparing to give a lecture on music in 19th century Glasgow, I did a rather random search in the Gale Historic Newspaper archive for a day around Christmas or New Year, to see what the Glasgow Herald was advertising as entertainment.

The date I looked at – ok, not so random – was 1 January 1880, which I knew (living as I do in Fife) was only a few days after the truly horrible weather associated with the Tay Bridge disaster (28 December 1879). Howling wind and driving rain, I thought, and possibly even a gloomy sense of national disaster, might damage Glaswegians’ sense of going out. It appeared I was wrong. New Year’s concerts around the city included all kinds of Scottish, classical and light music offerings, pantomime, variety acts, even a circus (Newsome’s Hippodrome and Circus). Amongst the choral pleasures were the Glasgow Choral Union, who were lining up to sing Handel’s Messiah at 1230pm in St Andrews Halls. Elsewhere in this edition of the Herald, you could read a review of another performance of the Messiah, in Hamilton, on Monday 29th December, by ‘the local Tonic Sol-Fa Choral Association’ recently ‘resuscitated’ and 70 in number, an occasion only marred by the non-appearance of the bass soloist and a smaller than usual audience deterred by ‘the tempestuous character of the night’.

In short, on a week of truly dreadful weather, amateur choral singers in Glasgow were out in force. For anyone not already aware of this, the 19th century in Scotland was one which saw a steady growth of amateur choral societies, including the Choral Union (formed in 1855 from the earlier Glasgow Musical Association) and the Edinburgh (Royal) Choral Union (in 1858). As well as giving citizens a chance to make music together, these organisations’ calls for scores also provided Scottish composers with opportunities to have new works performed. The Glasgow Choral Union, for example, ran an Overtures competition in 1888-9 that gave Hamish MacCunn a double win with The Dowie Dens O’ Yarrow and its companion piece, The Ship O’ the Fiend, both based on ballads (Oates, p.60).

In the early years of 20th century, a new choir appeared on the block, in the shape of the Glasgow Orpheus Choir, founded and led by the extraordinary Hugh S. Roberton. Roberton gave an account of the choir’s foundation in a concert programme note of 1915, recycled 10 years later by Grace Harvey in a review of the choir in The Musical Times. Roberton’s 1915 account talked about his coming to the choir after a less-than-successful period with a “recalcitrant and anaemic church choir”, and his introduction to the group of around 30 men and women initially called ‘the Toynbee House Choir’ (the choir in these early days was an offshoot of the Toynbee Men’s Social Club in Rottenrow). He asked them to sing a song they knew well:

“they threw it at me in slabs. It seemed to me (having come straight from that church choir) like the elements let loose in a hurry. It tore on its way as a tempest gone mad. It was the loudest noise I had ever heard or ever wish to hear in the name of music, and, to be frank, it was not musical; but there was heart in it” (Harvey, P.401).

It took some time to train the choir up, and not all of the early concerts were fine music. But Roberton’s aim was to keep that passion and emotion, while refining the voices and delivery. By 1906, when the choir moved to a new rehearsal premises in Collins Institute, and was renamed as the Glasgow Orpheus Choir, numbers had grown to around 70 singers. This new home gives some insights into the choir’s ethos and function in the lives of its members. The Collins Institute had been founded by publisher William Collins in 1877, with a range of facilities including dining, games, a library and a concert hall, intended to keep working folk away from the demon drink and to give them access to self-improving culture and education. Today, the building is part of the estate of the University of Strathclyde (see the HarperCollins Publishers Archive).

By 1925, the choir had 139 members, distributed more or less fairly evenly between SAT and B. Roberton insisted on regular attendance at weekly practice, which was necessary given that the choir by that point was giving over 40 concerts each season (Harvey, p.402), in venues all over the British Isles. As well as singing, adult choristers might also hope to be trained up as conductors under Roberton, and these alumni found their way into leadership positions in many choirs around Scotland. A junior choir was also in place to train up future choristers, involving over 100 young people not only in singing but also in dancing and (Kodaly would have been impressed) with clapping and other rhythm games.

The repertoire of the choir reflected wider British taste: Handel inevitably, and all the core classical repertoire by canonic composers such as Mendelssohn and Brahms, but also works by recent composers of the 19th century and early 20th century British musical renaissance, such as Holst, Charles Wood, Vaughan Williams, Stanford, Walford Davis, Dyson and Elgar. According to Harvey, ‘one of the aims of the choir has always been the fostering of the national spirit in music’, which meant that programming choices included many arrangements of Scottish songs, often by Roberton himself. The choir promoted competitions for original choral settings and arrangements of Scottish songs to add to their vast repertoire, with cash prizes and publicity in the British music press doing much to stimulate interest in this area. Contributions came from south of the border as well as from Scotland, and early winners included names like Francis George Scott with his setting of ‘Aye she kaimed her yellow hair’ (Anon, The Musical Times, 1919). Listening to archive recordings brings to us Glasgow voices singing with tremendous precision, both Scottish, and curiously ‘posh’ to modern ears.

Glasgow audiences flocked to hear both the adult and junior choirs in the vast space of the St Andrews Halls, to the extent that tickets were for a time balloted. Ticket sales alone kept the choir solvent for many years – something many modern choirs would wish were still possible, without additional sponsorship. Moreover, according to Harvey, ticket sales even generated a surplus which it gave to local charitable causes. The choir was, clearly, modelling citizenship, not only good singing.

Hugh Roberton’s contribution to the Scottish musical scene also included anthologies of song, and a house periodical, The Lute (implicitly, of Orpheus), with notes and more music. His own compositions included “Westering Home” and “Mairi’s Wedding” – which this writer learned at school as examples of ‘traditional folksong’, when clearly they weren’t, quite. Songs of the Isles (1937), an anthology which I assumed when it surfaced from a cupboard in my 1980s High School to be some kind of folkloric horde, turns out to have been written by Roberton. I can attest that his music found a place in my learning about Scottish song and singing.

When Roberton retired in 1950, after almost a half-century at the helm, the choir famously closed its doors, unable to imagine itself without his leadership. Hugh Macdiarmid, writing under his birth and journalist name of Christopher Grier, reviewed the book of reminiscences and clips that Roberton wrote with his son Kenneth in 1961, Orpheus and his Lute:

“What chiefly distinguished the Orpheus form other groups was not so much a matter of choral disciplines – though its rhythmic vitality and its verbal articulation were exceptionally good – as its quality of tone. … But there was more to it even that that. Sir Hugh was one of those dynamic, galvanizing characters who inspired his choristers not only to sing the music but to ‘live’ it.” (Grier, 1964).

Today we have great amateur choruses associated with the national orchestras and Edinburgh Festival, and also a National Youth Choir of Scotland. Before that, we had the Orpheus.

Further Reading

- “Advertisements & Notices.” Glasgow Herald, 1 Jan. 1880, Issue 12490. British Library Newspapers, Accessed 3 Mar. 2017.

- Anon, “Glasgow Orpheus Choir. Competition for Original Choral Settings and Arrangements“, The Musical Times, 60(917), (1919), p.370

- Michael De-la-Noy, ‘Roberton, Sir Hugh Stevenson (1874-1952)‘, Oxford Dictionary of National Biograph (2011)

- Christopher Grier, ‘Orpheus Choir’, a review of Orpheus with His Lute: A Glasgow Orpheus Choir Anthology’, The Musical Times 105(1454), (April 1964), 272

- HarperCollins Publishers Archive in Bishopbriggs, Glasgow – email in advance.

- Grace Harvey, ‘The Glasgow Orpheus Choir’, The Musical Times 66(987), (1 May 1925), 401-405

- Jennifer L Oates, Hamish MacCunn (1868-1916): A Musical Life (Routledge, 2013)

- Hugh S. and Kenneth Roberton, Orpheus with his Lute: A Glasgow Orpheus Choir Anthology (Pergamon Press, 1963)

- Hugh S Roberton, Prelude to the Orpheus introduced by F H Bisset (W Hodge and Co, Ltd, 1946),

Listening

- Glasgow Orpheus Choir Youtube channel