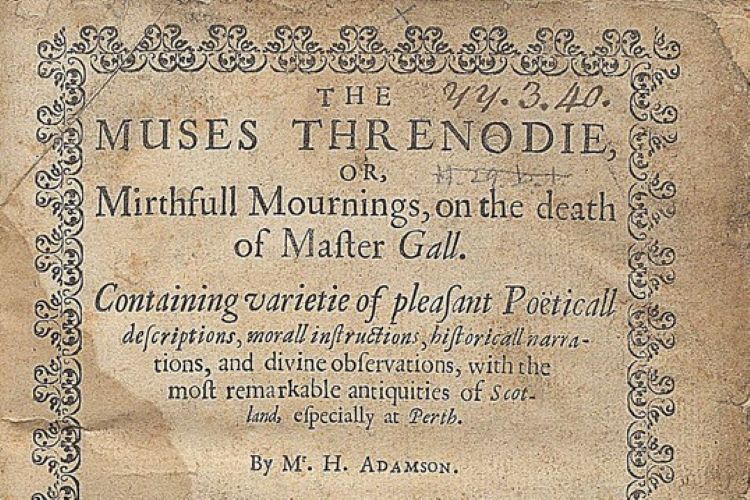

‘Reading Scotland before 1707’ is the title of the symposium co-hosted by the Folger Research library and the University of St Andrews, 6-8 May 2022. Attendees were given in advance some preparatory reading, including (from David J. Parkinson) a 17th century chorographic poem about Perth, The Muses Threnodie, or Mirthfull Mournings on the Death of Master Gall (1638).

With some trepidation – because this was described by historian Margot Todd as a ‘truly dreadful poem’ – I read it.

It’s not exactly Milton or Burns, but for musicians, this strange mock epic about 17th century Perthshire turned out to have quite a lot to say about music, as well as (en passant) golf, curling, archery and a generous scattering of history, myth and folklore about the beloved home-town of its author, Henry Adamson, Edinburgh university alumnus and local Perth schoolteacher. I found it a surprisingly rich in its evocation of the historic soundscape of central Scotland on the brink of the War of the Four Kingdoms. If anyone thinks Presbyterians were averse to music, they should read this.

A ‘threnody’ – as anyone in possession of a grammar school foundation in the classics would have known – is a song of lament and mourning. The poem presents itself as a memorial to one Mr Gall, a (real, historic) local merchant , clearly known to many in the town as a man of lively pastime, tall tales, and a deep knowledge of Perthshire folklore. Written to be read rather than sung, this is also a post-Reformation poem, and pulls no punches in its critique of the former monks and clerics associated with Perth’s Catholic monasteries and churches.

However, against my expectations, it is also a merry work, and makes joyful reference to music at many points in its ramblings. Perth, located at the intersection of the Scottish highlands and lowlands, was well placed to have its ears attuned to both Scots and Gaelic musical cultures. The musical references in this poem bring together sounds from both worlds.

The poem opens with a mock “inventory” of the random objects in an imagined (or possibly real) ‘cabinet of marvels’ belonging to the imagined speaker of the poem, George Ruthven. Various classical Gods are imagined as donating these objects: Apollo has contributed musical instruments, and these suggest an organology familiar to the Scottish poet: “his harp, his cithar, and mandore.” These sit alongside random shells, weapons, toasting forks, jewellery, books, children’s toys and curious objects associated with Gall’s domestic life and times.

- The countryside north of Perth, around Blair Atholl, was associated with Gaelic wire-strung harp playing, including two important historic harps, as discussed by Keith Sanger on the Wirestrung Harp.

- The cithar suggests the early modern ‘cittern’. Although the exact description of this isn’t clear from the poem, both English and continental examples survive in collections. See information on Rob MacKillop’s website or alternatively early examples of Italian guitar-like instruments in the collections of the University of Edinburgh.

- The mandore was a small, portable lute, easily carried and played by gentlemen – for a slightly later example, see again the Edinburgh University collections.

Amongst the children’s toys in the cabinet of marvels are a ‘gadareilie’ (a whirlie noise making disc on the end of a string), ‘a whisle’ and ‘a trumpe’. Perth children obviously were heard as well as seen.

From the older pre-Reformation world, we have ‘bels’ and ‘bones’. From country pursuits, some kind of a ‘hunting horn’.

These noise-making objects set up the reader in the poem that follows to be taken on a series of imagined journeys guided by the muses around the Perthshire countryside. The contents of the cabinet spark what the First Muse describes as a ‘doleful song’. It isn’t, actually; it’s lively if rough-hewn: a secular relic-inspired ‘requiem’ offered up by a Protestant poet with a tongue firmly planted in his cheek .

The First Muse looks at the accoutrements of archery, and is inspired to recall the first of many ancient battles fought in the vicinity of Perth. Initially, these are battles between local Scottish rival families:

“… then withal their maine

Their braikens bukled to the fight againe;

Incontinent the trumpets loudlie sounded,

And mightily the great bag-pipes were winded.”

Whatever the actual historical role of trumpets and Highland (‘great’) bagpipes on ancient battlefields, they clearly featured in the imaginary of this 17th century author.

Although clear-sighted about local divisions and shortfallings, this is ultimately a patriotic work. It places Perth at the centre of an mythological recognition of the Tay by the invading Roman armies led by Agricola as the new ‘Tiber’. It details the medieval wars of independence and the victories of Wallace and Bruce against the English, with Perth at the heart of these struggles: “no English since hath been thereof commander”. It celebrates James VI as the first king to unite Britain – explicitly united under a Scottish king, shaking off any sense of historical inferiority to England. And it celebrates more recent Protestant martyrs executed with ‘Saint Johnstoun riband’ (a noose) around their necks, “full of courage, worthie imitation”, “Martyrs all in their affection.” James’s son Charles I might have been warned that introducing the Anglican prayerbook to Scotland in 1638 would fly in the face of such pride. Maybe in Reformed Perth the age of Requiems was past, but there certainly was at least one very noisy poet to pen a secular alternative!

In a later passage, the Fifth Muse imagines the inhabitants of Perth mounting a musical defence of their besieged town. The extended metaphor (making music / making war) is stretched for humorous effect, but suggests to me similar burlesque battles mounted by Milton’s later 17th century epic, Paradise Lost to describe (impossibly) the battle between Heaven and Lucifer, and the parodies of heroism found in post-civil war Royalist mock-epic Hudibras by Royalist poet Samuel Butler. For those interested in music, it also suggests a poet familiar with actual performances of social music; an obvious knowledge of songs and reeling allow us to imagine the art of war as a ceilidh:

“Courage to give was mightile then blown

Saint Johnstons huntsup, since most famous known

By all Musitians, when they sweetlie sing

With heavenly voice, and well concording string.

O how they bend their backs and fingers tirle!

Moving their quivering heads their brains do whirle

With diverse moodes; and as with uncouth rapture

Transported, so doth shake their bodies structure:

Their eyes do reele, heads, armes and shoulders moveL

Feet, legs, and hands and all their parts approve

That heavenlie harmonie: while as they threw

Their browes, O mightie straine! That’s brave! They shew

Great phantasie; quivering a brief some while,

With full consent they close, then give a smile,

With bowing bodie, and with bending knee,

Me think I heard God Save the Companie.”

Inside the walls of the town, we find a world of Rabelaisian musicking, while outside, the enemy may roar like lyons.

Finally, there is also room in this poem for quieter music. The Sixth Muse reminds the reader of treasurers brought back from France, and this includes the aubade – a song of daybreak. The speaker remembers waking up Mr Gall with that Scottish wake-up call, a song called as Hey the day now dawnes. This is a poem whose antecedents are mentioned in Dunbar’s poem “To the Merchants of Edinburgh” (c1500):

“Your common mentrallis hes no tone

But Now the day dawis and Into Jone”

(The “common mistrels” in that earlier poem were the town band, normally pipers).

Gavin Douglas’s translation of Virgil’s Aeneid into Scots (1513) mentions the song:

“Tharto thir byrdis singis in the shawis

As menstralis playing, The joly day now dawes”

Alexander Montgomerie, poet, soldier, and courtier to James VI in the 1580s, wrote a lyric starting “Hey now the day dawis” which was probably at least in part an echo of this theme, and the Aberdeenshire Straloch Lute manuscript compiled c1627-9 has a setting of this lyric for lute. Clearly the opening words at least of this evergreen favorite, whatever its variant, was still known for its power to wake the ‘drowsie Fellow[s]” in Perth a few years later.

Off the singers of this the jolliest threnody go, singing into the Perthshire countryside: “some pastorall or sonnet sweet to chant.”

This pastoral turns into water music, as the singer takes to a boat with Gall down the Tay to a landing point at Friartown. Mr Gall urges more singing:

“Monsier, quoth he, I pray thee ease my spleane,

And let me heare that Musick once againe.

With Hay the day now dawnes, then up I got,

And did advance my voice to Elaes note,

I did so sweetlie flat and sharply sing,

While I made all the rocks with Echoes ring.”

There are natural soundscapes in this poem as well. The echoing winds around Windie Gowle “make the hollow rocks with echoes yowle”. If the head of Orpheus sang in death all the way to the sea, so did the imagined spirit of Gall.

In short, this may not be Milton, but it is musical, and on the edge of the war of the four Kingdoms, shows the Protestant Scots could sing, dance and play as lively a tune in verse as any English Cavalier.

Further Reading

- Henry Adamson, The Muses Threnodie, or, mirthfull mournings on the death of Master Gall, containing varietie of pleasant poeticall descriptions, morall instructions, historicall observations, with the most remarkable antiquities of Scotland, especially at Perth (Edinburgh, George Adamson, 1638), https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo/A03379.0001.001

- Gavin Douglas, The XIII Bukes of Eneados (1513)

- William Dunbar, To the Merchants of Edinburgh (c1500)

- David Parkinson, ‘”Mirthfull Mournings”: First looking into Henry Adamson’s The Muses Threnodie’, for the Sixteenth International Conference Medieval and Renaissance Scottish Literature and Language, University of Alabama, 24-30 July 2021 – https://www.researchgate.net/profile/David-Parkinson-2/publication/353837862_’Mirthful_Mournings’_on_First_Looking_into_Henry_Adamson’s_The_Muses_Threnodie/links/611484770c2bfa282a3a7a60/Mirthful-Mournings-on-First-Looking-into-Henry-Adamsons-The-Muses-Threnodie.pdf

- Margot Todd, ‘What’s in a Name? Language, Image, and Urban Identity in Early Modern Perth’, Dutch Review of Church History, 2005 https://brill.com/view/journals/nakg/85/1/article-p379_23.xml