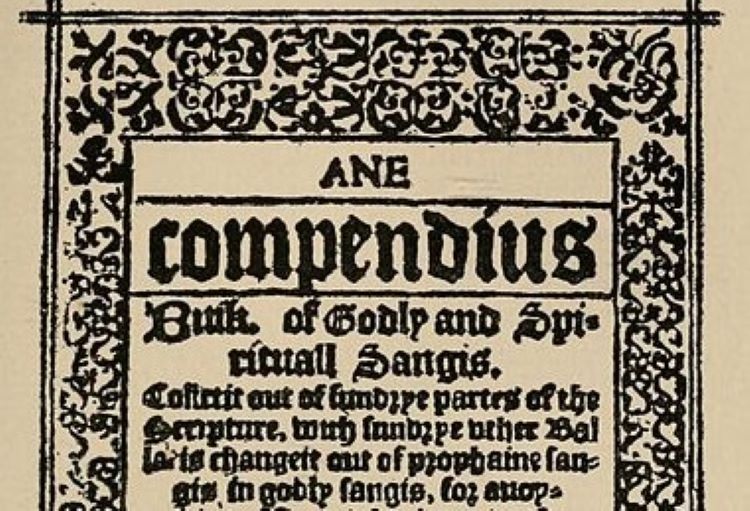

Image: cover of a 1600 edition of the Gude and Godle Ballatis, from Wikipedia / Project Gutenberg

Soundyngs has posted before about sources for Reformation psalmody, focussing on material curated carefully for use in church. But the 16th century reformers also knew that, left to their own devices, people outside of church would sing all kinds of diabolical songs. The earliest known printed edition of the Scottish anthology known as the Gude and Godlie Ballatis (or, ballads) appeared in 1565, within a year of the Scottish Reformation psalter, and was intended to provide god-fearing young men and women with songs to sing around their houses and workplaces. Unlike the psalter, much of this material uses vernacular Scots, which makes it a wonderful repository of native-language sacred verse, as well as a window into the creative energy associated with the early Scottish Reformation.

For those interested in the texts, the authoritative edition is the 2015 Scottish Text Society edition edited by Alastair A Macdonald (see Further Reading), a long-awaited update of an 1897 edition using an original 1565 source that the Victorians had not identified, prepared with critical notes comparing this with other early sources. This remains essential reading on the printing history, textual influences and cultural legacy of this work, and on the various figures associated with the original, both publishers and compilers, placing these in a book world that was carefully overseen by the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland, and post-Reformation politics of Edinburgh city (see, Macdonald). Macdonald would acknowledge, however, that there is probably much we don’t yet (or perhaps will ever) know about the publishing arrangements behind the Gude and Godlie Ballatis in the 1560s.

To some extent, the book was already rather old-fashioned – Lutheran rather than Calvinist. The idea of singing moral songs had become popular in Protestant circles inspired by the enthusiasm of Martin Luther for this kind of immersive teaching, from the 1530s in the British Isles. In England, Miles Coverdale produced a small book of around 40 songs, the Goostly Psalmes and Spirituall Songes (London: c1535) that drew on Luther’s work, and although this was banned in England in 1547, copies of this book circulated within the British isles along with other continental vernacular material, as the Reformation interest in singing congregations bore fruit and inspired other projects.

Although no edition of the Gude and Godlie Ballitis has been found in Scotland before 1565, it used to be thought that the Dundee Wedderburn brothers – James, John and Robert – were jointly responsible for this anthology. For many years all three were often credited with producing the Scottish Gude and Godlie Ballatis in some kind of manuscript or oral circulation, long before the 1565 printed book appeared, following statements made in the 17th century by David Calderwood in his History of the Scottish Reformation. However, the introduction to Macdonald’s edition includes a useful biographical summary of what is now known about the these men (Macdonald, pp.31-36). Macdonald, testing Calderwood, suggests that Robert was very unlikely to have been a Protestant, serving as he did as an (unreformed) priest in Dundee. James, the older brother, was a merchant with a known interest in poetry, but his eventual settlement in Catholic France also makes him an unlikely Protestant. Middle brother John, however, does seem to have some Protestant leanings; despite serving as a priest, he seems to have taken an interest in Lutheran verses in the 1530s and spent various amounts of time in continental exile in Protestant regions because of this. The Gude and Godlie Ballads have their roots, possibly, in John Wedderburn’s collecting, and possibly in oral or manuscript circulation of some of the material that found its way eventually into the 1565 book, but as he and his brothers were all dead by 1560, the book that finally appeared in 1565 was not their personal project.

The 1565 Gude and Godlie Ballatis was, however, a book that spotted a market opportunity and that hoped to ride optimistically on a wave of new, Protestant printing. The official music of the Scottish Reformation, used in church worship, was the Scottish psalter of 1564, a project led up by the General Assembly’s preferred printer, Robert Lekprevik. This, along with other material needed urgently by the Church of Scotland, must have tied up much of Lekprevik’s enterprise. However, a gap in the market existed for domestic material to be used outside of official worship, and this gap was spotted by Thomas Bassandyne the publisher (i.e. the person providing the financial backing for the project) and John Scot, its printer. It might be assumed that Bassandyne put the project together, or at least project-led, but in truth we have no evidence to say who led and who followed. This was Bassandyne’s first print project; Scot was established and experienced, but had been in trouble with the authorities in 1562 for printing a Catholic book, and fined heavily at that point; both men may have had reasons to position themselves more favourably within the changed confessional landscape of 1560s Edinburgh.

What appeared in print a year after the official psalter as the Gude and Godlie Ballatis was not in any way a copy of Miles Coverdale’s English 1530s work. Macdonald’s modern edition carefully tracks the lyrics appearing in this collection to a range of sources: many German Lutheran but including Danish, French, English and Scots sources that show the Scots of the period were aware of sitting in a main-stream European Protestant movement, by now also drawing on Dutch and Genevan, Calvinist translation method (Macdonald, pp.29-30). Critically, the language used for many of the songs was not English, but vernacular Scots. Macdonald’s also looks at the changes to the texts made in other early editions; by the time the book moved out of Scot’s printhouse to John Ros, for Henrie Charteris (1578), it had aquired the title page distinction of being printed by royal privilege. The book clearly sold well, passing through the hands of several publishers in the first 50 years of its existence. Dufflin’s book uses the 1578 edition, and is not such a reliable guide to the text variations that are found across different early editions.

The book was intended to ‘appeal especially to young persons who, however imperfectly acquainted with the scriptures and ignorant of Latin, would enjoy and gain spiritual benefit from these inspiring and energising songs’ (Macdonald, p.37). Genres represented vary from psalm adaptations, Lutheran hymns and prayers, carols and seasonal songs, complaints and satires (generalised rather than personal), and works of moral exhortation. It is a grand compendium of poetry in Renaissance Scots language, which has for that reason been mined in the centuries since it first appeared by Scottish poets as diverse as Alan Ramsay and Hugh MacDiarmid.

The original editions included words, but no notated music: which limitation is also, necessarily, present in Macdonald’s authoritative scholarly edition. Music was complicated and expensive to print, and although the General Assembly had ordered in special fonts for Lekprevik’s official psalter, his was possibly the only musical font in Edinburgh at the time. Musical font also required expert compositors; given Scot’s precarious finance situation, an edition with music must have been out of reach. Presumably, there was an expectation of oral resolution – fitting texts to already known tunes – although the 16th century book did not specifically cite these. This is that gap, for modern readers, that Ross Dufflin’s edition seeks to bridge. Dufflin sources tunes from contemporary Genevan psalters, from the English Broadside Ballad Archive EBBA, from the digitised material accessed through the ESTC, and from a range of other printed and manuscript sources held in libraries in Germany, France, Scotland, England, Ireland and America. Inevitably, Dufflin acknowledges that his allocations are rather more speculative than entirely authoritative, but explains that the method applied to identify possible models using a combination of meter matching and verse content would be consistent with the method used by early readers. This is called ‘contrafacta’ – fitting preexisting tunes to new texts – and had been a practice for centuries. In some cases, Dufflin is able to match lines closely to material with contemporary music printed. Dufflin argues that helping us, today, to lift this material out of the page and into song helps us imagine ‘what sixteenth century Scots would have experienced’ (Dufflin, p.xvii). This reviewer agrees that this is interesting and useful aspiration.

Performance notes in Dufflin’s introduction provide some guidance on historic Scots pronunciation and suggests that the songs would most likely have been sung in unison, monophonically, rather than in the more elaborate kinds of setting found in the near-contemporary Wode psalter (Dufflin, p.xviii). The tunes printed in the collection are shown using bar lines to clarify phrases, which is not as contemporary sources would have been presented but is useful for a modern novice singer, and keep the proportional notation as clear as possible to help these readers understand what the tune would sound like. Transposition of some tunes has been used to ‘provide a median range for singers’ (Dufflin, p.xxii). Combined with beautifully clear print presentation from the publisher, these songs are ready to sing.

While Macdonald’s text edition has extensive scholarly endnotes, Dufflin places his notes alongside the tunes and text, which provides readers with a more compact information set, as well as helping Dufflin to clarify why he chose the tune he did for this text. This feels like being walked through the songs by a knowledgeable enthusiast, which is an attractive scholarly model and potentially very useful for teaching this material.

Potentially, therefore, this book could be used by singers wanting to recreate what an early modern performance of this material would have sounded like, or as a teaching resource, helping students to understand the oral world of the Scottish Reformation. My one wish is that the publisher, A-R Editions, would price this book more accessibly. Admittedly they aim to produce scholarly research editions for researchers rather than in the first instance, performers or classroom teachers. But a retail price label of $260 for a 196-page softback book is a barrier to steep for smaller institutional libraries, and for performers and students, daunting, which is a pity because it would be grand to lift this material from the eye to the ear. Aquiring permission to copy excepts for use in UK teaching has also proven difficult, as the package isn’t part of current consortia packages used by this reviewer’s library. The publisher has, I think, been careful to donate copies to some libraries where local readers may have a research interest in the material, which is very helpful – find one in a libary near you – but this isn’t as straightforward to roll into teaching as it might have been, had it been differently packaged. A-R Editions aren’t an educational charity, then, but I suppose we need to remember that even Bassandyne and Scot needed to make enough money from sales to pay the printshop. Presumably the modern classroom use would return to early modern orality, the teacher singing to the students using the library copy of Dufflin, hoping that the students might, line by line, respond.

Further Reading

- EBBA – The English Broadside Ballad Archive at the University of California at Santa Barbara.

- David Calderwood, The History of the Kirk of Scotland, written in the 17th century, edited by Rev Thomas Thomson (London: Wodrow Society, 1842-9)

- Miles Coverdale, Goostly Psalmes and Spirituall Songes (1635) – Taylor Facsimile Edition from Oxford University library digitations, 2021.

- Ross W Dufflin (ed.), Gude & Godlie Ballatis Noted (Middleton: WI: A R Editions, 2022)

- Robin Leaver, ‘Goostly Psalmes and Spirituall Songes’: English and Dutch Metrical Psalms from Coverdale to Utenhove 1535-1566 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991)

- Alastair A MacDonald, The Gude and Godlie Ballatis, Scottish Text Society Fifth Series no.14 (Boydell Press, 2015)

A-R Editions also print scholarly editions of the following Scottish material:

- Hamish MacCunn, Complete Songs for Solo Voice and Piano, edited by Jennifer Oates

- William McGibbon, Complete Sonatas edited by Elizabeth C Ford (another 3-figure price) but individual parts for subsets of this may be purchased more cheaply.