Review: The Life of a Showman: David Prince Miller

A review is normally of a new book, but in this case, the book has been around since 1856. However, a recent self-published edition has appeared with an historical essay and notes by Martin MacGilp on this curious character. This edition is a labour of love rather than an academic monograph, but it does invite us to think about the kinds of musical experiences working class folk might have had in the early years of ‘summer holidays’ (*clinging on to the fast-vanishing memory of these). Miller’s writing is hard work, but MacGilp’s essay helps to clarify the narrative.

In another departure from normal operations, this is not a book about music, but it does give some insights into the mid-Victorian entertainments of working class people in Scotland, and perhaps helps to explain why the high-cost world of opera, for instance, struggled to find a permanent home in 19th century North Britain. This sets a context to understanding why Music Halls came to be so important in Scottish musical culture. Heaven knows, it was hard enough to keep low cost theatre on the boards.

Amongst other interests, Martin MacGilp is a puppet enthusiast and has a general interest in the kinds of popular entertainments that 19th and early 20th century holiday makers might have encountered on summer holidays to the beach resorts of Scotland. His list of publications includes a work on ‘The Carrick Marionettes’ of Girven, Ayrshire, and the sometimes violent adventures of a highly dubious character called Mr Punch as he appeared to children in Scottish fairgrounds and Music Halls in the days before safeguarding checks on all those working with children and vulnerable adults. If you want to think more widely and not necessarily musically about the glories of the Scottish seaside holiday in history, I recommend to you Eric Simpson’s lovely wee illustrated book on what olden times northern beach holidays used to be like, alongside MacGilp’s puppet pieces (see Further Reading).

Anyway, back to David Prince Miller, and his ‘managerial struggles’. Miller was Londoner by birth although through his Scottish father, he was attracted up north (p.208). He spent his early life on the road as a magician, fire-eater, monologist, coordinator of pantomimes, and (at least in his aspirations) also a writer; not altogether a chap to whom you’d lend a pound expecting to see it again. His view of life is generally, that his talents deserved more luck than he was served by fortune. For those interested in Scottish music, the interest in the book lies in the framing of his adventures within a 19th century entertainment culture linking working class people all over Britain.

Summer hiring fairs rather than beaches structure the timetable of his early opportunistic journeys around the border towns, crossing frequently between Scotland and England. From Carlisle to Dumfries was a short journey, but one that almost defeated Miller, who, travelling on foot in a storm, became thoroughly lost before eventually making it to the Dumfries summer fair (p.71-2). Many Scottish towns still have summer fairs weeks, a carry-over of the older agricultural summer and autumn hiring fairs that ran from June to early November, allowing labour to travel to whereever agriculture and fisheries needed additional seasonal labour, and giving days out for other kinds of trades. Mindful of the uncertainty of Scottish weather, our man was keen to perform indoors, in the Dumfries Trades Hall, hiring this out for 7 shillings a day, and heating it with coals bought by the performers themselves. He often travelled on foot, although he also owned a wagon for his long-suffering wife and worldly goods, and if nothing else was available, this vehicle also served as a stage. On a trip to Kelso, he was lucky enough to perform first at the Assembly Rooms at the Cross Keys pub and then was taken up to the grand house at Mellerstain (p.94) to perform magic tricks for the gentry.

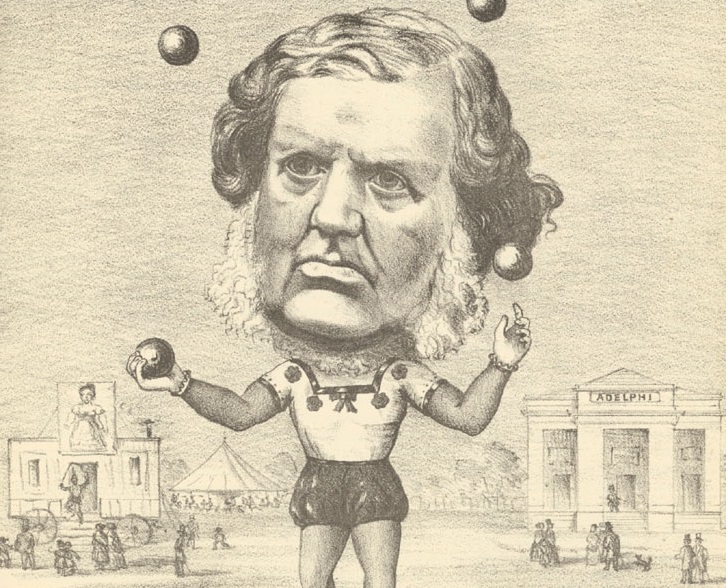

July 1839 brought him up to Glasgow for the first time, at least by his own account, although Miller was often not very reliable on dates (p.99-100). From there, he undertook an extensive circular journey to Stirling, Perth, Dundee, St Andrews, Cupar, Kirkaldy, Dunfermline and Airdrie, before returning to what was now Scotland’s largest city. This section of the memoires describes other entertainers who went on to make their own contributions to Scotland’s local theatres. Many acts seem to be dramatic ‘impersonations’ of character types – such as that given by Harry Shaw, whose ‘Scotch characters’ seem to have been in the vein of Harry Lauder’s later successes in the Music Hall. Very gradually, Miller moved up the social ladder of venues from trades halls to the Theatre Royal in Edinburgh. Very gradually, the shows grew in scale and ambition from fire-eating and magic tricks to fully-cast dramas with lurid titles, which required scenery and costumes. Rumours of his death (p.140), appearing from mid-way through the book, were greatly premature at least in medical terms if not levels of aesthetic reputation. From a booth on Glasgow Green, he eventually built and managed the Glasgow Adelphi Theatre on Glasgow’s Saltmarket (p.223), opening this rapid-build wooden building in 1843 (p.243). The Adelphi at this point was one of only two licenced theatres in the city – a rags from riches success story – until it burned down in 1848. It was not insured.

Licenses for theatres in Scotland were not readily available, as MacGilp’s editorial essay explains, which is one reason why opera struggled to take off in the country, although light operettas, and concert arias, were billed alongside some speciality musical acts. Miller, as the manager of a city theatre, was well-enough networked to be able to get a ticket to hear Jenny Lind, the Swedish Nightingale’s, tour of Scotland in 1847 (p.141-2) but other than a note about her ‘warbling’, his account of this occasion does not teach the reader a great deal about her repertoire or audience. Needless to say, she was not performing in his venue, although Miller did manage to book in a famous actor, William Charles Macready, in late 1847 (p.248). Alongside this he found time briefly to run a pub and run benefit concerts in the City Halls to supplement the income from the theatre.

After his theatre burnt down, a reduced Miller toured with a show based on his own life, and became a writer for Punch magazine, authoring some pieces on street entertainers, before opening a second Adelphi in Coatbridge, and then a third theatre in Dumbarton in 1864, on the unfortunately named ‘Risk Street’ (p.259). Overextended, he went bust. In the last year of his life, in 1872/3, he was again planning to open a new theatre in Glasgow, to host circuses and novelties. He is buried in the Glasgow Necropolis, beside the Cathedral, with a rather fine memorial stone.

One thing to note is that in order to set up a show as a travelling entertainer, Miller needed to get bills printed afresh in the towns he visited (e.g. p.110), with venue details as these were fixed. Those interested in entertainment advertisements might find some ephemeral traces of this kind of throw-away poster advertising in the University of Glasgow Scottish Theatre Archive collection, although I suspect most of the paper evidence for this would have dissolved in a few good west of Scotland rain showers. The Glasgow Story website has also some material from this submerged iceberg of ephemera.

Everyone seems to have drunk like a shoal of fish in the Scottish light theatre world of the 19th century, which might explain some of Miller’s narrative gaps and vagueness about dates. A caveat about the book as a chronicle is the lack of clear dating: we ramble from year to year as much from town to town, sometimes doubling back over the order of events. I rather wish the editor had included a dated itinerary. It would also be great if Miller had thought to pay more attention to other entertainers’ acts other than his own – but I suppose the entrepreneurial showman writes his own poster. There is more in this book of off-stage than on-stage entertainment, but it does give a glimpse into the fragile nature of early popular entertainment, and the toughness of its travelling performers and impressarios.

If you read this book, which is very reasonably priced, perhaps do so alongside a work about the Scottish music hall – maybe J H Littlejohn’s The Scottish Music Hall 1880-1990 (1990), which gives a town-by-town summary of these venues, starting with Glasgow, and taking in all corners from Fife to Inverness. Littlejohn’s book is also written by an enthusiastic and knowledgeable niche-writer, and like MacGilp’s book, was printed in a slightly out-of-the-way Scottish press. Littlejohn provides a good summary of the many venues that could host orchestras, bands and singers as well as clog dancers, magicians, fire-eaters and comic sketches in the century following Miller’s demise. Many Scottish singers had their roots in this world of Scottish variety. I can’t find out much on the web about Littlejohn – if anyone reading this knows or knew him, please contact me!

Further Reading

- David Prince Miller, ed. Martin MacGilp, The Life of A Showman and the Managerial Struggles of David Prince Miller (1856) (Inverness: Gilpress Publications, 2023)

- H. (Jimmy) Littlejohn, The Scottish Music Hall 1880-1990 (Wigtown: G. C. Book Publisher, 1990)

- Eric Simpson, Wish You Were Still Here: The Scottish Seaside Holiday (Amberley Publishing, 2013)

- The Glasgow Story website has some information about Miller and the Adelphi

- Scottish Music Hall and Variety Theatre Society – originally the Harry Lauder Society, a rather horrible website from the assault of which my eyes are still reeling, but this and their magazine Stagedoor has some wee gems about popular Scottish entertainment written by folk who either remember it themselves, or have good links back to those who were there. Their Facebook page, for those who want to join their discussions, is also worth a visit.

- University of Glasgow – Scottish Theatre Archive – see the University library Archives and Special Collections, probably a visit for a deeper dig than the website yields.

Very enjoyable piece!

Thank you – I’ll think of this guy any time someone wants me to invest in their pop-up theatre venture!