Scottish musical identity has steered a course through national history navigating between the devil’s fiddle and the psalm book of John Knox, and it’s about time that Soundyngs had a grapple with the latter, as it is an important musical repertoire for many Scots. This post draws attention to a new online resource for the metrical psalter, created by researcher Tim Duguid: a digital Splitleaf psalter.

A Potted History of Scottish Psalmody

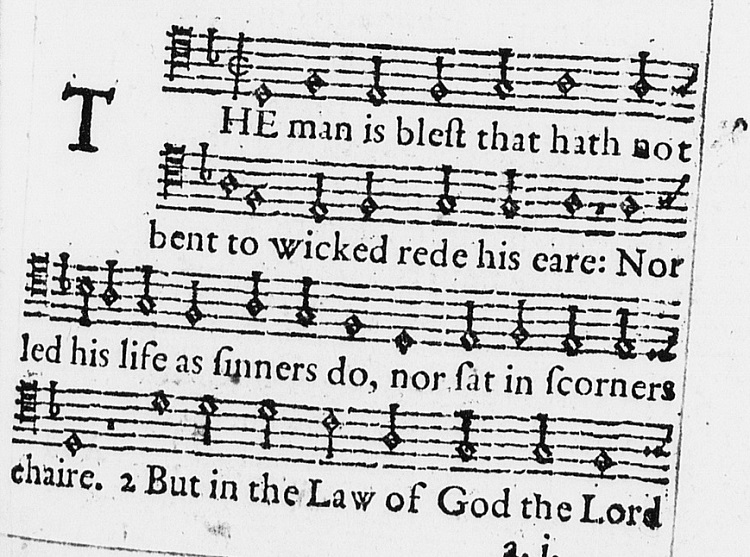

The Scottish Reformation was achieved by some fast-footed action on the part of Protestant nobles in 1560, who enacted the Reformation Act of Parliament between the death of Mary of Guise and the home-coming of her daughter, the young Mary Queen of Scots, from France. In 1562, the Church of Scotland General Assembly instructed that every church in the land should have access to John Knox’s Forme of Prayers and Ministration of the Sacraments, which included the psalter (text only, no music). Mass print-production of this, coordinated by Robert Lekprevik of Edinburgh, was to enable literate Scots to own their own copies of the psalms. By 1564, the Scots had this psalter in their hands, containing all 150 psalms set to music using the metrical, stanzaic translation model of the Genevan psalter. The language used was English, not Scots, as many of these translations had been developed by Scottish protestant exiles working alongside their more numerous English counterparts in Geneva and Strasbourg. Nevertheless, it encouraged whole congregations to sing in church – men, women, and children.

There were differences between the Scottish and English psalters, as Timothy Duguid, researcher in digital humanities at the University of Glasgow, has written about extensively. Initially, the Scots had access to a wider range of meters and hence a wider range of potential tunes than the English had under Elizabeth I. However, within a few decades, the pragmatic realities of teaching new tunes to congregations, and the fact that some Genevan tunes work in French but not so well for English texts, meant that a much smaller number of ‘common tunes’, and hence a rationalisation of metres and translations, had occurred. The road to the mid-century civil war was pathed by Scots protesting against the introduction of an English (Anglican) prayerbook; amongst other activists was Jenny Geddes, who famously pitched a stool at the head of the minister who tried to introduce the new prayerbook in St Giles Cathedral in Edinburgh. Clearly, the Scots by this point saw these words as non-negotiable in their national worship. United against a common enemy, there was a brief period following the execution of Charles I when the Scots and the English worked together in committee to produce a new metrical psalter; in the event, only the Scots adopted it, but this, the 1650 Westminster Psalter, became the principal basis for sung worship in the Church of Scotland from that time forward to the 20th century.

For most people worshipping in the Church of Scotland, the psalms were sung syllabically, in unison, using simple, strophic tunes. Inspired by the popularity of stanzaic balladry in everyday life, this new Protestant music created translations and new melodies that could be sung by all in church worship.

Variant traditions of Scottish psalmody do exist. For a short time after 1560, some composers and singers continued to set psalms using more elaborate polyphonic techniques for private, domestic use (see, for example, the manuscript part books associated with the Wode Psalter of St Andrews, some of which is available online thanks to research led by Jane Dawson at the University of Edinburgh – another project in which Tim Duguid has assisted). What ‘unison’ means in practice may also be more complicated than the print record alone might suggest. In the Gaelic-speaking Highlands and Islands, “unison” singing should really be described as “heterophonic”, as lined-out verses led by a precenter may be followed by the congregation responding simultaneously with individually ornamented versions of the psalter tunes, resulting in a high level of variation framed within the whole congregation ‘unison’ offering. Gaelic uses assonance rather than end-rhymed consonance, which lends itself to exploration of vowels and vocalisation. However, some authorities have also suggested that in the absence of choirs, early congregations throughout early modern Britain might all have sung like this: that the Hebridean heterophony (and also found in some churches in the US) is in fact a survival from the early days of the Protestant Reformation (Terry Miller, 2009). Whatever the historical narrative might be, it is a style that makes audible the balance between individual and community worship.

Notwithstanding any musical variance, the text – the Book of Psalms from the Old Testament – is vitally important, and the metrical translations are central texts to Scottish music and literature. For some Protestants even today, psalms are the only text that should be sung in church. For others, even the unchurched, psalms are still amongst the songs committed to heart: psalm 23, ‘The Lord’s my shepherd’, features in many funerals, and shapes many people’s experiences of collective musical consolation in times of grief.

Scottish Psalters Today

The Church of Scotland – the established church in Scotland – from the later 18th century began to adopt a rather wider repertoire, including hymns and psalm paraphrases. The approved national hymnals for a long time had the psalms in a separate section (1898 and 1927). The 1972 3rd edition of the hymnal, although containing some ‘favourite’ metrical psalms integrated within the hymnal, did not include the full psalter, which led in many churches to a decreased use of this core repertoire. However, a decade-long project on music in worship, led by modern hymn composer John Bell, resulted in the 2005 4th edition, known as CH4; in this, the complete metrical psalter was restored to the front of the book, which restored its integrity within one, consolidated hymnal.

However, the Calvinist – and Knoxian – tenet that only the psalms (and a very few New Testament canticles) had scriptural grounds for singing in church ensures that psalmody and nothing but psalmody continues to be heard in many Free Presbyterian, Free Church Continuing, and Reformed Presbyterian (Cameronian) churches today, often unaccompanied according to historical use, using either modern versions of the Genevan Psalter, or the metrical psalms embedded in Sing Psalms (2003 revised edition), produced by the Psalmody and Praise Committee of the Free Church.

The Split-Leaf Psalter (2021)

The genius of the Reformers in creating a new repertoire for congregational singing lay in realising that the metrical forms of popular balladry – i.e. counting syllables per line, and repeating this for each stanza of a translated psalm – could be fixed so that any tune written in that pattern could be fitted to any translation using that meter. That made it possible to use, pragmatically, the same tune for different texts, allowing congregations to absorb the new tunes piecemeal, although in practice many psalms are strongly associated with particular tunes in local usage. A split-leaf psalter (e.g. Sing Psalms, the Free Church psalter) cuts the pages in half with the upper half carrying the tune and the lower half the text: users can flip to match a tune of their choice with the text of the psalm they want to sing, matching meters. Tim Duguid has created an online version of this approach, the Split Leaf Psalter under a creative commons license. This is a really useful resource for people interested in historical tunes, as Duguid has drawn on three absolutely core historical psalters: the 1564 Forme of Prayers; the 1635 Psalmes of David in Prose and Meeter (the first fully harmonised metrical psalter in Scotland, in particular the 30 Common Tunes); and the 1650 Westminster Psalter. Have a look!

Further Reading and Online Resources

- The Splitleaf Psalter – edited Tim Duguid (2021)

- The forme of prayers and ministration of the sacraments &c used in the English Church at Geneva, approved & received by the churche of Scotland whereunto are also added sondrie other prayers, with the whole psalmes of David in English meter (Edinburgh: Robert Lekprevik, 1564) – see digital information and link to digital copy through the USTC.

- CH4 – Church of Scotland Hymnal – information here – including psalm recordings prepared for congregational use during Covid-19.

- Tim Duguid, Metrical Psalmody in Print and Practice: English ‘Singing Psalms’ and Scottish ‘Psalm Buiks’, 1547-1640 (Ashgate Press, 2014)

- Tim Duguid’s research page at the University of Glasgow – links to more articles on psalms.

- Terry Miller, ‘A Myth in the Making: Willie Ruff, Black Gospel and an Imagined Gaelic Scottish Origin‘, in Ethnomusicology Forum 18(2), 2009, pp.243-259.

- Miller Patrick, Four Centuries of Scottish Psalmody (Oxford University Press, 1949) – not the most up to date history, but for a clearly themed chronology, still an accessible read

- Sing Psalms, (Free Church of Scotland Psalmody and Praise Committee, 2003) – information page.

- Wode Psalter – manuscript part books, compiled in the 1560s and 70s – see online resources hosted by the Church Service Society.