Soundyngs posted earlier in the year about Celtic Connections, Scotland’s premier international festival for Celtic music. The summer months are almost on us, and with them, a whole new, modern traditional festival ecology. Some of these follow the pattern of commerical outdoor festivals throughout the UK, aiming primarily to entertain, possibly also to revive local tourist revenue. Others have their roots in Gaelic-language fèis, which place a higher priority on education and preservation of Gaelic-language traditional culture for local people. The same artists often flow between both kinds of events, which are mainly to be distinguished by their side programmes and support networks. Both varieties do significant cultural work in packaging traditional Scottish music culture for modern audiences.

The Festival

While park festivals may take their inspiration from the open-air hedonism of the 1960s and likes of Woodstock, Glastonbury and Latitude, in Scotland, there is also a distinctive tradition of working-class, “everyman” kind of festival which has its roots in the popular reaction against the more high-brow classical-music agenda of the Edinburgh international festival. Those who spurred the development of the Edinburgh fringe were often champions of specifically Scottish indigenous culture, particularly from a left-of-centre political stance. The People’s Festival Ceilidhs were part of this reaction, backed by the likes of Hamish Henderson and Hugh MacDiarmid (see Angela Bartie and Eberhard Bort, in Further Reading, below).

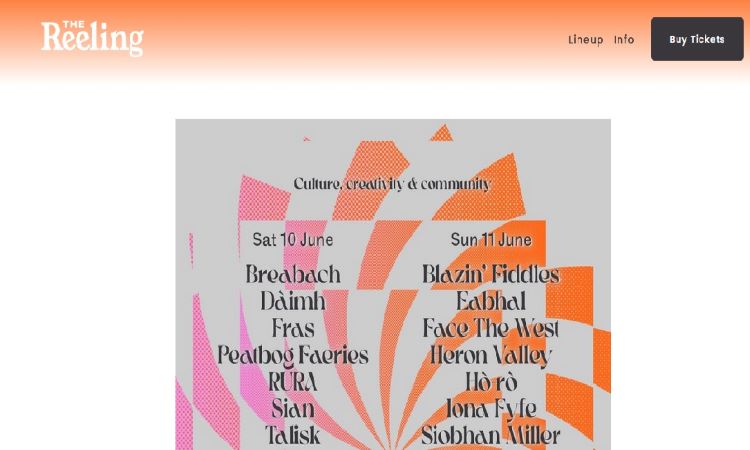

Into my social media feeds this month has popped a brand-new festival that sits within this tradition of “people’s festivals”: The Reeling, “Glasgow’s new trad music fest’ according to its website, planned for the weekend of 10th and 11th June. Like many summer festivals, The Reeling will be hosted by a local park (South Glasgow’s Rouken Glen Park). Unlike the infamous and currently ‘resting’ environmentally-destructive Scottish pop festival “T in the Park” (1994-2016), visitors to the ‘sustainability’ conscious Reeling festival are not encouraged to camp. Its target audience is probably more home-crowd than the international profile of Celtic Connections: website information flags the Glasgow bus services which would get you to the venue.

There is nothing particularly special about Rouken Glen, other than this part of Glasgow might not hitherto have had much happening locally by way of music festivals. Rouken Glen Park, according to its local government-maintained website, was a hunting estate gifted by James V to the 1st Earl of Montgomery. In the 19th century, it was developed by Glasgow industrialists, who were responsible for much of the modern tree planting, before it was eventually gifted to the ‘people of Glasgow’ in 1906. A fairly typical (for local parks) listing of amenities include formal gardens, tennis, table tennis and basketball courts, an exercise circuit, and regular opportunities to bounce on a bouncy castle. Very much, local leisure amenities for local people. And now, it has a music festival, which is being more widely advertised. It will be interesting to hear after the event about its first audiences: the percentage uptake from Renfrewshire locals versus visitors.

Although festivals can encourage locals to enjoy and take pride in their home ground, most festivals aim also to attract tourists and visitors to an area. For example, for those prepared to brave a CalMac ferry this spring, the late-April Mull Music Festival – which advertises itself as FREE – could be very attractive. Mull Festival events run in hotels and bars, and attendance doubtless covers costs in bar and other hospitality trade profits. It’s no accident that a local hotel – MacGochans of Tobermory – is the main sponsor and central venue. Quite a bit of academic research has been carried out into the relationship between these local festivals and tourism, which might be a useful economic factor in Scotland’s recovery in this post-covid period (see some instances in further reading), Simon McKerrell and Jasmine Hornabrook’s work in particularly suggests a model of working closely with local communities, in order to understand both the impact of these festivals, and possibly how best to develop them as a locally embedded infrastructure.

The Fèis

According to Thomas McKean, who wrote about this in 1998, the Gaelic fèis is a relatively modern development with its foundations not so much in emulation of commercial music festivals, but in endeavours to help revive and celebrate spoken Gaelic. Father Colin MacInnes and Angus MacDonald of Barra and Vatersay, in 1981, are widely credited to be early organisers of events in this new performance tradition, although a glance at the various websites suggests that in the Northern Isles of Orkney and Shetland, similar annual events sprang up at the same time. These entrepreneurially organised ‘gatherings’ take the place of traditional informal gatherings in domestic taighean cèilidh (visiting houses), which had in older times been the places where traditional songs and music were shared inter-generationally.

Gaelic fèis events are different from the mainly competitive festivals for school children which can be found both in the Anglophone parts of Scotland, and also, as part of the network of national and regional Mòds, in the gàidhealtachd. The national Mòd has its origins in a late 19th century response in emulation of the Welsh Eisteddfod, and has done good work in preserving tradition, although possibly finds it more difficult to respond to the more dynamic nature of newly created material in the traditional idiom. The Barra Fèis founded by MacInnes and MacDonald is still running, and now advertises on its website a bank of musical instruments and lessons available throughout the year. Following on the footsteps of Barra, since 1991, there has been a national network of specifically Gaelic festivals advising members about funding, training, insurance and more. Funded by Creative Scotland and now based in the Highland capital Inverness, this network is at the heart of activities curating Gaelic medium art and culture. Since 2017, Glasgow has also been included in the calendar, running its fèis in mid-April.

The summer festival as an alternative to the summer fair?

Despite my attempt to separate out Festivals and Fèisean into more commercial vs more curatorial traditions, each festival and fèis will have its own unique character and history. Some festivals run for years. Others have shorter histories, filling short-term niches before vanishing. Some are internationally important and attract international as well as home performers (the winter Celtic Connections is probably the premiere model). Others, such as Skye Live (running this year 11th to 13th May) are more regionally focussed, although popular bands such as Talisk pop up in multiple programs all over Scotland and throughout the year – sensibly, because a band needs to play all year. Rather as Scotland’s summer fairs had touring rides – teacups, rollercoasters and bumper cars – which travelled from point to point as the rolling calendar of events across the region, so do Scottish bands take to the roads.

What makes a local festival unique may have a lot to do with its specific geography, and the way in which it makes a geography special to festival-goers. Festival venues may build on social gathering patterns associated with other kinds of summer entertainments: county agricultural fairs and highland games. The weekend of music comprising Skye Live, for example, is located at Am Meall (aka ‘The Lump’) in Portree, also the venue for a long-standing Highland Games later in the year. Other festivals make a green field into a new gathering point – as seems to be the case for The Reeling and Rouken Glen Park. Some festivals – such as SEALL or the Fèis an Eilein (Skye Festival, but not to be confused with Skye Live) have many subsidiary venues scattered across a wider regional area, and help to gather multiple localities into a wider area identity – and to map the path from point to point for both locals and visitors.

Making music local may also be a reaction against modern technological distribution and global de-localisations. The burgeoning world of festivals is happening alongside the meteoric rise of streaming services, which allow musicians to produce music relatively cheaply and distribute it very rapidly to listeners, but usually without much financial gain to the creatives, and with listener communities formed virtually and without the kind of human-to-human connection associated with the ethos of ‘traditional’ music. For musicians, streaming platforms are audience-building exercises rather than primarily income generating: the income generation comes from the live performances, and hence, the growth in events bringing artists together; potentially, local artists can be integrated within a wider national economy of festive music-making. And for audiences, this brings the live, human contact that traditional music lovers crave.

Mapping the Festival

I’m looking for, and not quite finding, a book or even a website that could bring together and profile all Scottish summer festivals, thinking ethnographically about the ways in which they gather audiences into specific interest groups (classical, contemporary, folk, Highland, rock, etc) as well as thinking about different sites, and possibly even different missions. Such a book would be firing at a moving target, as the ecology of festivals is shifting all the time, but still, there is clearly such an appetite for this kind of all-you-can-eat one-point-stop entertainment, it merits a closer look. A baton to whoever wants to write this…

A Sample of Spring and Summer Folk and Traditional Music Festivals in Scotland might include (and almost certainly isn’t exhaustive):

Highlands and Western Isles

- Fèis Bharraigh – Barra Festival. Running since 1981 and said to be the first of the modern fèisean. a celebration of music, story telling and language, taking place in early July

- Fèis an Eilein – the Skye Festival, also known as SEALL. A year-round programme, but particular high-spots in mid-July and in November (the winter “Festival of Small Halls”). This festival takes advantage of the creative energies associated with Sabhal Mor Ostaig, now part of the University of the Highlands and Islands, working in partnership with local government and tourist agencies.

- Skye Live – in mid May. An eclectic mix of modern rock and pop, and more traditional bands.

- Mull Music Festival – in late April, out of Tobermory.

Northern Isles

- Orkney Folk Festival – based on Stromness and other venues across the islands, mostly indoor, scheduled for in late May, and in 2023 celebrating it’s 40th year of running. This is one of the larger festivals, with an international line-up,

- Shetland Folk Festival – a month earlier than Orkney, and one year older (this year is its 41st anniversary), running in late April, and thus, definitely an indoor festival, mostly hosted at Lerwick’s Islesburgh Community Centre. Again, drawing in artists from around Scotland and some international acts, alongside local artists such as Da Langstrings and Da Loose Ends.

- Shetland Accordion and Fiddle Festival – in October, not really qualifying as a ‘summer’ festival, but one last blast before the onslaught of the northern winter.

Lowlands

- Auchtermuchty Festival – this used to take place annually in the home town of Jimmy Shand, in mid August. The website is at the time of writing this post a bit short of information and I wonder if this festival has fallen on hard times….

- Fife Sing – at Falkland and Freuchie, which is quite near to Auchtermuchty, and I wonder if this is where Auchtermuchty went to – running in mid-May annually, featuring bothy and other ballads, stories and more.

- Knockengorroch – advertising itself as “a bigger festival in a smaller pot” and “the first greenfield festival of our type in Scotland”, this festival in Galloway in the deep south west is another ‘Celtic diaspora’ festival, and is now in its 25th year. Definitely one for visiting campers, with the landscape as a point of focus. Running in late May – arguably, Scotland’s most beautiful season.

- Tradfest – in Edinburgh in late April and early May – traditional music both from Scotland and around the world. Very much a city festival, Edinburgh’s springtime answer to Glasgow’s Celtic Connections. Although Celtic Connections is still the big beast, this one also has a lot to offer.

Further Reading and online sources of information

Bartie, Angela, The Edinburgh Festivals: Culture and Society in Postwar Britain (Edinburgh University Press, 2014) – particularly chapter 3 on the creation of the ‘Fringe’

Bort, Eberhard, ‘Tis Sixty Years Since: the 1951 Edinburgh People’s Festival Ceilidh and the Scottish Folk Revival (Ochentyre: Grace Note, 2011)

Gamble, Jordan R, ‘Exploring the Relationship between Arts Festivals and Economic Development in Rural Island Regions: A Case Study of Scotland’s Orkney Isles’, in Event Management 26(2), (2022), pp.349-367, https://doi.org/10.3727/152599521X16288665119486

Jolliffe, Lee and Baum, Tom, ‘Event Tourism Partnership Evolution – Evidence from the Highlands of Scotland; in Tourism Today 4 (2004), pp.7-20 https://www.cothm.ac.cy/_files/ugd/79301e_88714efe4d0d45eba23d5b130c62cb9f.pdf#page=8

McKean, Thomas, ‘Celtic Music and the Growth of the Fèis Movement in the Scottish Highlands’, Western Folklore 57(4) (1998), pp.245-259 https://doi.org/10.2307/1500262

McKerrell, Simon and Hornabrook, Jasmine, ‘Mobilising Traditional Music in the Rural Creative Economy of Argyll and Bute, Scotland’, in Creative Industries Journal 15(3), (2022), pp.237-256 https://doi-org.ezproxy.st-andrews.ac.uk/10.1080/17510694.2021.1928420

Stevenson, Lesley, ‘Scotland the Real’: The Representation of Traditional Music in Scottish Tourism’, PhD, University of Glasgow, 2004 https://theses.gla.ac.uk/1297/

More Websites