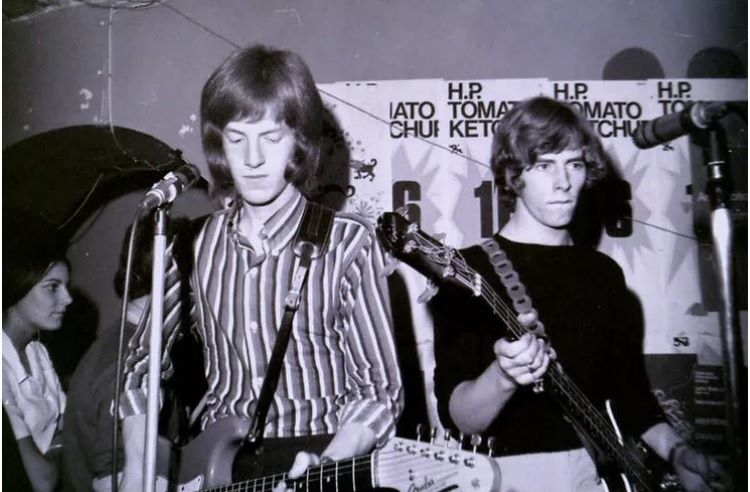

Image: The Bay City Rollers in Edinburgh before they were famous, from Edinburgh Live, photo credit Len Cumming.

This post thinks about the role of those involved in the Scottish heritage industry in curating through story-telling in popular books. Yes, this work is commercial – and definitely commercial, in no way academic. But it’s also a record of local identity, and that it exists to do so makes it the kind of ephemera that potentially comprises a source for future historians. It boils into one wee concentrated sweetie images that focus collective memories of the sounds and sights in the stories it presents – a bit like a postcard from the past. As my own personal contribution to the anecdotes contained herein, I remember in 1983 being dragged around Edinburgh’s guitar shops in search of a guitar by a friend from home while we were both ostensibly “down south” for a university open day. So, my earliest semi-adult memories of the city are marked by a personal map of music shops and the distance between them measured by the arm-strain from amp-lugging. This sort of experience, albeit presented in the form of guitars in the hands of more expert players, is what the authors of this book help to document.

Edinburgh’s Greatest Hits: A Celebration of the Capital’s Music History was written during the COVID-19 crisis, when many venues were closed, and is the joint project of two commercial enterprise: Edinburgh Music Tours (an outlier of the commercial firm GlasgowMusicCityTours.com) and Edinburgh Music Lovers, which similarly aims to help curate entry points to musical and other cultural experiences. The world of COVID was pretty bleak for these kinds of business: writing this little book represents the authors’ hopes for an eventual return to in-person normality.

So, this wee book is essentially a commercial for a research project of the future; but it’s also a reach out for personal connection, and uses to that end, ethnographic narrative: people, telling their subjective stories about places, a journalistic approach that has left its mark on more academic prose, I might suggest.

On that basis, what can this tell us about Edinburgh’s historical relationship with music?

The authors are keen to convince readers in section 1 (‘Local Heroes’) that Edinburgh had parallels to many of the greatest musical celebrities of the 20th century. Well, that’s unabashedly subjective, but cheese-on-toast narratives are fair enough in this context.

- Leith had its own answer to Elvis in the form of Jackie Dennis, ‘the Lilt with the Kilt’ (p.1);

- Edinburgh’s female competitors to the Beatles in Hamburg were The McKinlay Sisters Sheila and Heanette (p.5);

- The Incredible String band (p.6-7) shared the Beatles’s fascination for importing oriental sounds into commercial 1960s rock and pop;

- If you are a Jimmy Hendrix fan in Edinburgh, then consider searching out recordings by Edinburgh-raised guitarist Bert Jansch (p.8-9);

- Perhaps more reasonably, we are reminded of the global sensation that was Edinburgh’s own tartan-clad Bay City Rollers in the 1970s (pp.10-11);

- If punk in the 1970s was more your thing, you are reminded of Edinburgh College of Art bands like the Rezillos (p.24-25);

OK; this isn’t a robust historical critical comparison. But it does set up a window showcasing local pride in creative and new music-making. In case you need reminding, and fairly on-target, globally-famous duo, the Proclaimers, brothers Craig and Charles Reid, were born in Leith (pp.26-27).

The book points out in section 2 (‘Wish We’d Been There’) some venues you might have visited before Covid closed doors to hear bands and singers. The People’s Festival Ceilidh of 1951 gets a look-in, in Oddfellows Hall on Forrest Road (p.34). Other venues range from student bars to the unlikely appearance of Led Zeppelin in the shabby-chic plush auditorium of the King’s Theatre in 1973 (p.37).

Edinburgh is also a place to which famous artists come, briefly stay, and go (‘Famous Residents’, p.39-46), and also, once (in 1972) hosted the Eurovision Song Contest (so, not just a figment of the imagination of those making the 2020 Eurovision Movie featuring Will Ferrell and Rachel McAdams).

A section on ‘Venerable Venues’ lists places of all sizes and shapes from Sandy Bell’s folk pub, to the air-hanger-like Playhouse. This section could be seen as an Edinburgh parallel to the loving list of Glasgow places curated in Dear Green Sounds (Waverley Books, 2015) although for this reviewer, Dear Green Sounds is a more profound read. This reader wonders why the book doesn’t take the obvious tack of linking anecdotes to a map or itinerary – although having wondered, of course, that addition would take away the need to get them to manage your walking tour for you. Still, armed with this book and a map of Edinburgh, you could probably put together your own series of walks, whether record shops, labels or venues was the theme, or just a wish to explore the musical memories of a particular part of the city.

‘Gone but not forgotten’ lists some live music venues that no longer exist, including locations I remember from my teenage visits to the city. A final section on clubbing in the 1990s and 2000s looks forward wistfully to these and other venues reopening post-covid.

Why does this wee book matter? Well, not necessarily for its profound historical depth. However, as a snapshot of the collective memory of Edinburgh people and heritage-workers about music in Edinburgh in the later 20th and early 21st centuries, this book is both a collective scrapbook, and an index to why music matters so much to Edinburgh’s cultural and economic life. A 100 years from now, it will be seen as an historic document, even if it’s authors claim to think of history as rather dry and dusty.

Further Reading

- Edinburgh Music Lovers

- Glasgow Music City Tours

- Jim Byers, Fiona Shepherd, Alison Stroak & Jonathan Trew, Edinburgh’s Greatest Hits: A Celebration of the Capital’s Music History (Birlinn Books, 2022)

- David McLean, ‘Rare Edinburgh Photos Emerge or original Bay City Rollers Line-up playing Old Town club in 1968’, Edinburgh Live, 4 March 2022 and Len Cumming’s photo archive in the same publication