‘The Ringing Stone of Tiree’ in J.A. Harvie-Brown and T.E. Buckley A Vertebrate Fauna of Argyll and the Inner Hebrides (Edinburgh: David Douglas, 1892), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9532852

In August 2022, Soundyngs posted about imagining historical soundscapes. A particular use of this imaginative work is relevant to sacred music, where the resonance of places might have been important to enabling and encouraging spiritual encounters in religious worship.

This post catches up with some work that has focussed on this challenge: modern secular technology, in conversation with the sacred past. James Cook’s Linlithgow project has now been published.

Working with early music group the Binchois Consort, a recent Edinburgh University-led, AHRC-funded project (‘Space, Place, Sound, and Memory: Immersive Experiences of the Past’) recreated in the recording studio two ‘virtual reality acoustic environments: Linlithgow Palace, with Renaissance sacred music by Robert Carver (Cook et al, 2023).

The resulting recording was intended for site-based installation at Linlithgow palace. It imagined a choir singing, and an organ placed high above the listeners, who might be scattered throughout a complex site with side chapels running off the main space.

Taking the architecture of the building into consideration resulted in various kinds of changes to the music, such as accentuating bass reverberation (p.111), which in turn gives insights into how best to position singers (basses in the middle, higher voices at the side, of the choir) singing such music. The authors suggest that the statues of saints “would be animated by sound” (p.112), the music creating an immersive “charged space” connecting worshippers with icons.

To acquire more realistic architectural modelling, the team worked with Historic Environment Scotland to take LIDAR (laser) measurements of the palace, layering onto this what they could posit about doorway spaces, processional routes through the spaces, and the possible impact of doorway drapes and fabric which are referenced in royal treasurer accounts (p.114, 116). Glass windows and plaster walls were also simulated, with painted tiles similar to those now found in Stirling (p.117). Determining the placement of the choir itself was complicated by the small size and narrowness of the chapel, and suggested a standing group of singers, possibly without fixed choir stalls.

The actual recording took place in an anechoic chamber in the University of York rather than onsite, where dry sound could be captured using close-mic recording: less pleasant for singers used to performing in an actual resonant space, and clearly a challenging experience for all concerned on how to produce something that sounded musically vibrant and blended (p.121/2) but the resultant CD is worth listening to. The article also ponders on the acoustic impact of the Reformation, when saints, drapes, and organs were often removed from churches, possibly rendering sacred spaces more resonant. Soundyngs wonders what impact that might have had for singers of psalms after 1560.

Ours is a technical age, and possibly technology takes us further away from sacred experiences – it’s rather unusual for technology to get us closer to sacred resonance, as this project has done.

Yet if we look at other ancient sonic spaces in Scotland, we find plenty of evidence that resonance has been important to religious ritual, even where that technology is lying around fields rather than located in sound laboratories.

- Sounds made within the Camster Cairns of Caithness and Easter Auquorthies stone circle in Aberdeenshire amplifies low frequency sounds. This is particularly useful for drumming, which build in intensity when projected by certain stones producing “peculiar echoes”. Research has suggested that even if these effects weren’t necessarily designed in, this would have become an affordance of the ritual experience (see, Watson and Keating. P.326). Investigation found that this uses the principles of ‘Helmholtz resonance’ (the amplification of sound using standing waves in confined spaces, also found in blowing across bottles); continuous sounds generated from within the cairns result in powerful infrasound waves (low frequencies), which are sensed as uncanny or more than simply natural.

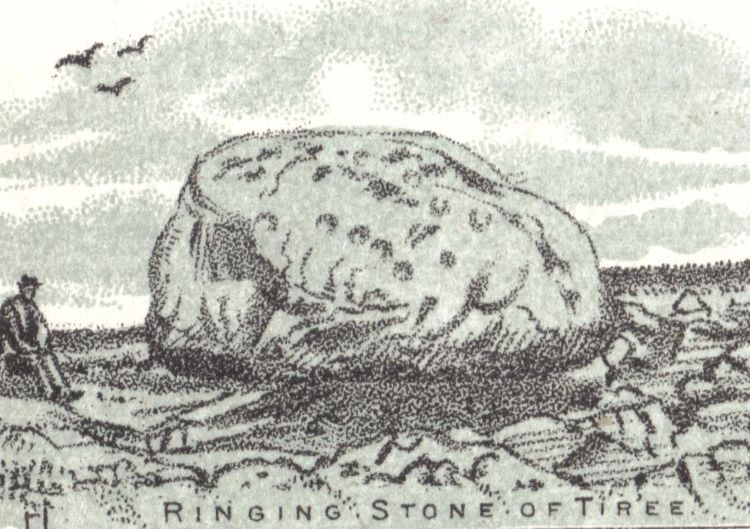

- Ringing rocks, or lithophones, are rocks made of crystals aligned in such a way that the rock resonates like a bell when hit with another, smaller, stone. The scientific explanation for this phenomenon puzzled geologists for a long time and varies depending to the composition of the rock. Rock gongs exist all over the world and are often sites of sacred significant for indigenous communities. One that found its way into a stone circle on Arn Hill near Huntly was possibly deliberately chosen for the ritual possibilities of its sonorous capabilities (Purser, 2007). Another, possibly the most famous of Scotland’s ringing stones, is the Tiree Ringing Rock, “Clach a’ Coile” or the ‘Kettle Stone – at Balaphetrish, which is covered with ancient cup marks that suggest many people have hit it over the centuries. Legend has it that if it is ever removed, Tiree will sink beneath the sea (Provan, p.130-131)

Both indoor and outdoors, it’s worth listening to how spaces affect sound.

Further Reading and Listening

- James Cook, Andrew Kirkman, Kenneth B McAlpine, and Rod Selfridge, ‘Hearing Historic Scotland: Reflections on Recording in Virtually Reconstructed Acoustics’, in the Journal of the Alamire Foundation 15(1) (special edition Rhythm in the Arts in the Late Middle Ages, II), 2023, pp.109-126

- Cook et all, ‘Space, Place, Sound, and Memory: Immersive Experiences of the Past’, UK Research & Innovation website

- John Purser, Scotland’s Music, ‘Rocks and Bones’, BBC broadcast 7 Jan 2007

- David Provan, ‘Note on the Occurrence of Carboniferous Fossils and Chalk Flints in the Superficial Deposits of Tiree’, in Transactions of the the Edinburgh Geological Society, 1914, pp.129-131

- Aaron Watson and David Keating, ‘Architecture and sound: an acoustic analysis of megalithic monuments in prehistoric Britain’, Antiquity 73, (1999), pp.325-36

- ‘Ringing Stone: cup marked lithophone’ in the Tiree and Coll Archaeology Database, Isle Develop CIC