I had a very enjoyable visit to Perth this month looking at 18th century flute music, following up on Elizabeth Ford’s book The Flute in Scotland from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century and equipped with the catalogue of the Atholl Collection in the A K Bell Library. The library is a great place to work – well lit, and sociable. I am grateful to the team there for making me welcome.

Ford’s excellent book surveyed holdings in the NLS and several other important libraries, but does not specifically engage with flute music in the Atholl Collection. It was clear that Lady Dorothea Steward Murray’s 19th century findings support Ford’s theory that flute playing was wide-spread in 18th and early 19th century Scotland.

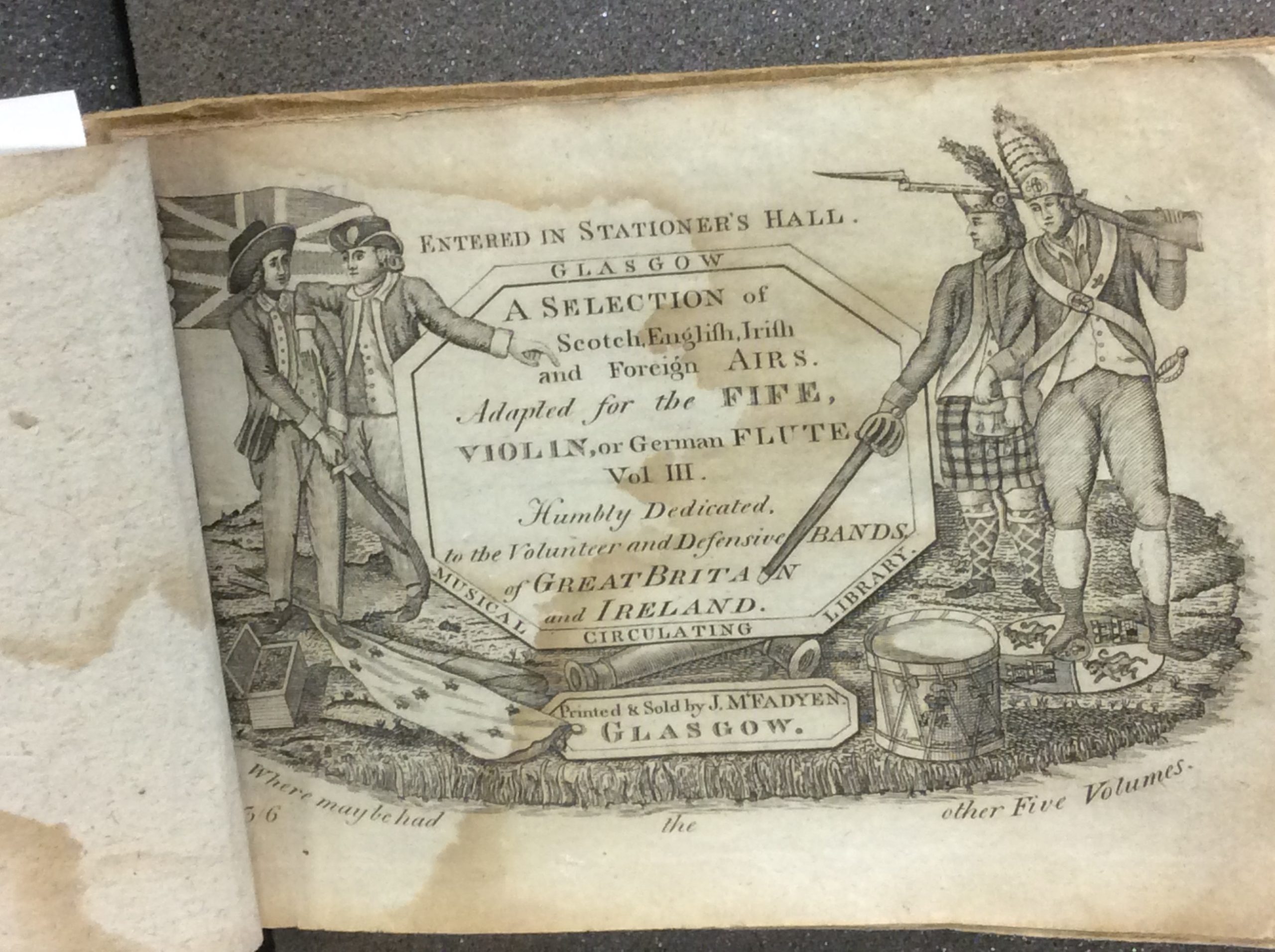

While Ford’s book provides a national survey, particular private collections may reflect local patterns of interest and use. The material at Perth includes material from the last quarter of the 18th century and early 19th century that might reflect the Atholl family’s interest in military music. As is well-known, the Duke of Atholl has – uniquely in the UK – the right to raise troops and lead a private regiment. Between 1777 and 1783, the 4th Duke of Atholl first raised a regiment to be part of the British army fighting initially in the Americas and then in India. From 1839, the regiment was resurrected under the 6th Duke of Atholl and served as a bodyguard to Queen Victoria during her stays in Scotland in 1842 and 1844. Although the flute music in the collection is for social rather than active military use, front pages in several books make the association between flute playing and contemporary soldiering very clear.

The following items on inspection seemed to connect strongly with the British military musical culture of the later 18th and early 19th century:

- Airds Selection of Scotch, English, Irish and Foreign Airs adapted for the Fife, Violin or German Flute, humbly dedicated for the Volunteer and Defensive Bands of Great Britain and Ireland vol.3 (2nd edition, 1788, sold by McFadyen, Glasgow) – military material includes the ‘Royal Scots March tune’, the ‘South Grenadiers March’, ‘Gibralter Balloons’, etc. [*see featured image] Aird’s collection ran to 5 volumes, and at least 2 editions.

- Macleod’s Collection of Airs, Marches, Waltzes and Rondos, for two German flutes W Hutton (Edinburgh, s.d.) – titles of pieces reflect the late 18th century military campaigns e.g. ‘Lord Cornwallis March’ (named after the leading General of the British forces during US War of Independence), and Buonoparte’s (sic) ‘Grand Parade March’ and ‘Buonaparte’s Return to Paris from Elba’ (sic).

- John Miller His Book of Music for the Fife – a manuscript book marked 1799-1801 on the inside cover, possibly compiled by a soldier based in Perth barracks, containing military marches including e.g. the ‘13th Regiment of Light Dragoons March’, ‘Tipperary Militia Quick March’, ‘Smack of the Whip: A Retreat’, etc. The final pages of the book also contain unexpectedly arrangements for flute of Scottish psalter psalm tunes, suggesting that these may also have been played recreationally.

- Johann Georg Christoph Schetky (1737-1824), A Collection of Scottish Music consisting of Twelve Slow Airs and Twelve Reels and Strathspeys arranged for a military band. Schetky was a German flutist based for a time in Edinburgh, and this has parts for a standard Germanic military wind band of flutes, clarinets, horns, trumpet and bassoon. The cover page notes that ‘the bass drum, triangle, tambourine etc will easily be added in the lively airs as the judgment of the leader shall direct’, and the bookseller advertises himself ‘where military instruments are manufactured in the best manner and on reasonable terms’. This volume is dedicated to ‘his excellency Earl Moira, Commander in Chief of his Majesty’s forces in Scotland’. Francis Rawdon-Hastings, the 2nd Earl of Moira (1754-1826) was an Anglo-Irish peer who served in the American war and then in the French revolutionary wars of the 1790s; he entered politics as a Whig supporting Irish issues including Catholic emancipation, and became commander in chief of the military in Scotland in 1803. Although the catalogue suggests 17??, the dedication suggests this music was published sometime around or shortly after 1803.

Other items in the catalogue not inspected but also relevant would include works by General John Reid (1721-1807) – military man and leading light of the Edinburgh Musical Society, whose bequest endowed the Reid Chair of Music at the University of Edinburgh. His compositions are designed more for the drawing room than for the battlefield, but show how these instrumental skills readily transfer to other kinds of social playing. See: Reid, Second Sett of Six Solos for the German Flute or Violin (London: Oswald, 1762) and Sett of Minuets and Marches, inscribed to the Rt. Hon. Lady Catherine Murray (London, s.n., 1770).

There is much else in the collection to delight flutists interested in Scottish tunes, including flute tutor books and music for the drawing room. Social dancing is also clearly an interest, as might be expected, combining both Scottish and British fashionable material. Bland and Weller’s Collection of Scotch Dances & Reels with their proper figures for the Violin or Flute with a Bass for the Piano Forte or Harpsichord as performed at Court, Bath, and all Polite Assemblies (London, 1797) provides – in the fifth volume which I inspected – useful choreographies as well as music for fashionable new tunes such as ‘Go to the Devil and Shake Yourself’ and ‘The Mysteries of Udolpho’. This last title references Ann Radcliffe’s Gothic horror novel first published in 1794. Any dance based on that might be worth recreating with a caveat that the female heroine of the novel spends most of it in fear of her life!

Further Reading

- Gary West, ‘Scottish Military Music‘, chapter 24 from his A Military History of Scotland (Edinburgh University Press, 2012), 648-668