Featured Image: Kirkcudbright, by Kenny Lam, from Visit Scotland Website

In Soundyngs’ last post, I discussed the song collecting activity of William Macmath, and a particular manuscript in his meticulous hand now held in the Hornel library in Broughton House, Kirkcudbright. This post takes the story forward beyond Macmath’s fieldwork assistance to Francis James Child on Scottish border ballads.

Hornel’s collection, which puts Burns’s song collecting in its local Galloway and contemporary Scottish context of songwriting. was put together with the help of local publisher and author Fraser Miller who, like Macmath, was a local authority on the songs of Dumfries and Galloway. I was told when I visited Broughton House that Miller offered to help Hornel compile “the perfect local library”. When Macmath died in 1922, Miller helped Hornel to purchase both Macmath’s own notes and material he owned.

An item of national importance that entered the Hornel library at that point was the Mansfield Manuscript, which Macmath had bought in April 1900 in an Edinburgh book auction.

Image: receipt of 1900 Mansfield Manuscript purchase by Macmath (author’s own photograph)

The Mansfield manuscript is a late 18th century manuscript written in a hand considerably less neat than Macmath’s, containing around 200 songs and ballads from diverse areas of Scotland, including the borders. It appeared too late to help Francis James Child, who had died in 1896, with the final stages of his English and Scottish Popular Ballads (5 vols) appearing posthumously in 1898.

When Child and Macmath were working on the Child Ballads, the Mansfield manuscript had been thought lost, known only from a sales catalogue listing made in 1853 of the estate of Thomas Mansfield (an Edinburgh accountant). Several references from the first half of the 19th century (by Robert Chambers (Scottish Songs, 1829), David Laing and C K Sharpe) suggested this was a collection of songs originally written down in the 1780s by a ‘lady living in Edinburgh’, possibly a Miss St Clair (see Miller, 1935). Robert Chambers had written that “Miss St Clair” was a friend of Mrs Catherine Cockburn; Laing used the manuscript in notes for his 1839 revised edition of the Scots Musical Museum; Sharpe, also in 1839, had noted that the material was from ‘a lady’ from the previous century (he suggested some 70 years back – rather an overestimate) (Miller, 1935). Frank Miller suggests that the lady in question was Elizabeth (Bess) St Clair, daughter of Charles St Clair of Herdmanston, Advocate of Edinburgh, who married a Lieutenant Colonel James Dalrymple in 1773.

Bess has a hasty and large hand, which is legible although not so easily read as Macmath’s meticulous transcriptions. A fun reference in the manuscript is a note about her own appearance at an Edinburgh entertainment:

Bess St Clair was there so charming & gay

As red as the morning & bright as the day.

Although her manuscript has many well-known traditional songs, it also contains a lot of topical, political material, giving an insight into the politics of polite Edinburgh society. Bess was clearly at home in the social circles of Hanoverian Edinburgh (her husband was, after all, a serving army officer), but the manuscript also contains Jacobite material, reflecting lowland Scots’ ongoing fascination with the glamour of the old cause. In one song, ‘The Pretender’s Manifesto’, to be sung to the tune of ‘Clout the Cauldron’, the song’s narrator (‘a Hero to my trade, and truly a most leal prince’) holds out a series of promises to protect ‘liberty of law and religion’:

I’m sure for even years & mair

Ye’ve heard of sad oppression

And this is all the good ye got

O’ the Hanover succession

For absolute power & popery

Ye ken it’s a’ but nonsense

I here swear to secure to you

Your liberty of conscience. (Mansfield M/S., p,113ff)

Whether this is trustworthy or perhaps intended to be delivered ironically, is not entirely transparent from the manuscript alone.

The Mansfield manuscript also contains a unique version of “The Flowers of the Forest”, a ballad associated with the Battle of Flodden (1513), and, importantly for the Hornel collection with its focus on Robert Burns, many songs of interest to Burns including “Jenny’s a’ wet, poor body”; “Here’s to the dance of Dysart”, the original of Burns’s “Hey Ca’ Thro”; “Ca’ the ewes to the knows” (pictured below); “Com’n through the Rye, poor Body”; and “O now I’m in the Low Country”, a Jacobite song that appeared in volume 5 of Johnson and Burns’s Scots Musical Museum (Miller, 1935, p.21-22). The lyrics in many cases are a little bit broader in their references to sex than many of the bawdlerised versions that made it into parlour song books in the 19th century.

Ballads from Mansfield that were unknown to Child include ‘The Laidley Worm’, a supernatural monster story from Northumbria. See Steve Gardham’s article in Folk Music Journal, and Ronnie Clark’s recent editorial work on this material, for more detailed discussion of what this source has that Francis Child missed reading.

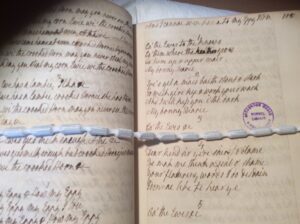

Image: Mansfield M/S ‘Ca the Ewes’ – author’s own slightly blurry (sorry!) photograph

Further Reading and Listening

- Broughton House and the Hornel Library – National Trust for Scotland Visitors Page

- Ronnie Clark, ed. The Mansfield Manuscript: An Old Edinburgh Collection of Songs and Ballads (Glasgow Ballad Workshop, 2015) – original in the Hornel Library. The editor’s website has a contact address for copies.

- Steve Gardham, “The Mansfield Manuscript: An Old Edinburgh Collection of Songs and Ballads,” edited by Ronnie Clark, in Folk Music Journal, 11(1), 2016 pp. 74-76.

- Frank Miller, The Poets of Dumfriesshire (Glasgow: James Maclehose and Sons, 1910)

- Frank Miller, The Mansfield Manuscript: An Old Edinburgh Collection of Songs and Ballads (Dumfries: Thos. Hunter, Watson & Co, 1935).

To read Soundyngs post 1 of 3 on Broughton House click here

To read Soundyngs post 3 of 3 on Broughton House click here (live from 2 October)