Soundyngs recently reviewed a book on 19th century popular entertainment. Today’s post reviews a picture-book history of Scottish dance halls before there were DJs and turntables, when people still danced to live band music. Many Scottish bands of the 1950s, 60s and 70s had their origins in this kind of night out. While conventional musicology might want to concentrate on ‘the music’ alone, it’s worth saying that wider ethnomusicology would want to look hard at the behaviours and cultures that make music possible. In the 1970s, the engine room of live music was dancing. And, possibly, on the social behaviours that this encouraged and inculcated.

Waverley Books, who published this book, is an imprint of the Glasgow-based Gresham Publishing Company. Their output is geared towards the popular end of the book market: as its entry in trade directory Publishing Scotland notes: “history, nostalgia, fiction, humour, travel writing and cookery”, and “high-quality notebooks” backed with approved tartan and in some cases, also designed around famous Scottish songs. Active since 1997 in this imprint, they have a good grasp of the contemporary market for all things past and Scottish, and a keen instinct for how to tell a story using images as well as few but the right words.

Being a popular rather than an ‘academic’ press means that Waverley can be visually creative in presenting the past. Soundyngs is a big fan of the wonderful Dear Green Sounds: Glasgow’s Music through Time and Buildings (2015) (see Further Reading), which has contributions from some of the best modern writers on different periods of Scottish history and genres, and which takes the reader on a vivid trek through venues as diverse as Glasgow Cathedral, The Scotia Bar, and King Tut’s Wah Wah Hut.

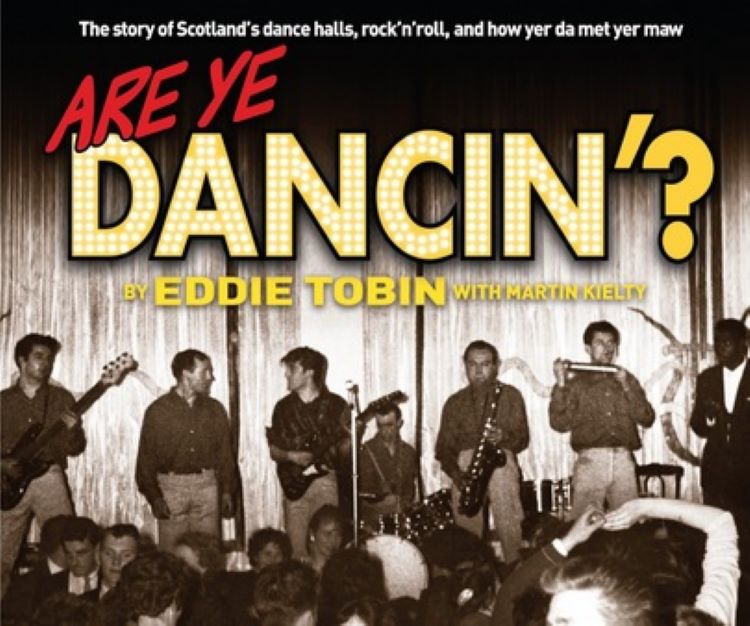

Similarly illustrated, this earlier book commissions eye witnesses rather than academic writers. Of the two authors associate with Are Ye Dancing? the “professional writer” is Martin Kielty while the “headline name” is Eddie Tobin. Both have had careers which mean they probably also “knew all the right folk”, and both understand from the business side what people wanted from a night out. Kielty is more of a musician: the former manager of the Sensational Alex Harvey Band, he is also a music journalist, story-teller, and a regular television presenter on STV. Eddie Tobin is the impressario (to use the language of the 19th century): he was, in the 1970s, the manager of many entertainment acts including Fife rock band Nazareth, the youthful Midge Ure and even at one point, Billy Connolly when that national hero was starting out as a folk singer who told good jokes. Latterly Tobin turned his business mind to managing pubs and clubs around Glasgow, and possibly there is more to that than can be told in a book like this: Tobin once survived being shot at close quarters on the doorstep of his home (see The Herald, 2006). More incredible still, somehow, Tobin was commercial manager for players on both sides of the Celtic and Rangers divide (see Tobin’s introduction). His direct connection with the world described in this book was a period spent managing the music club side of The Apollo in Glasgow, formerly Green’s Playhouse, expanding from the core ballroom space known as “Clouds”, and from there helping to set up other venues in central belt Scotland.

Kielty and Tobin present a glimpse into a night out before the modern club. Its chapter headings are a bit less transparent than Dear Green Sounds, using lines from interviews which hook you in like half-heard snatches of sound from an old wireless programme: “you could actually tell the time by the tune they band were playing” (chapter 2); “he started tooting the horn – they’d got their dental braces tangled” (chapter 9). These flag up the method of history-telling, which first summarises trends before illustrating these using excerpts from ethnographic interviews with people who were there in various capacities at the time. These brief truncated one-sided conversations are just fascinating. A criticism of the book is that the speakers, although named, are not given deeper biographies: all we have of them is the sound-bite sized quote. This is a shame: a more ambitious book would also have included a short biographical appendix that would have been able to place these contributors more generously. If tapes exist somewhere of these interviews, they should be put into some national archive facility.

Early chapters show that dance culture has deep roots in Scottish culture. Before there were clubs, there were ceilidhs in local spaces, and local players who could reproduce both traditional tunes and music connecting with more international dance styles. In the 1920s and 30s, charabanc buses began to take folk from rural places into the bigger towns for dances, bringing opportunities to meet lovers from beyond their immediate communities. WW2 brought American soldiers and jazz music, although people continued to dance using traditional steps and music styles.

By the 1950s, however, dance bands were playing international forms of dance music. Jazz, blues and eventually rock band musicians could travel the country on a developing circuit of venues, networking drill halls, boys brigade halls, and trade halls into regular dance nights. Bands were quite sizable, with an instrument line-up that included kit drum, guitars, saxophones, trumpets, horns, string bass, piano, and less regularly, singers: a format modelled on North American big bands and ‘jazz orchestras’.

North American influences also eventually brought in rock and roll. Discussion of Lonnie Donegan and his skiffle band forms an inevitable bridge between indigenous forms of popular music and more international dance crazes, the latter thriving despite evident disapproval from older commentators. The arrival of ‘big stars’ touring from outside Scotland – English artists like Cliff Richard and Tommy Steele – encouraged a shift towards celebrity culture – listening as well as dancing. In chapter 6, January 1963, the Beatles in their early days played in Dingwall, Aberdeen, Bridge of Allen and Elgin.

Dance choreographies changed with growing commercialisation of the “hit list”: jive become rock and roll, which gave way to the twist and then increasingly various and less structured forms of moving. Older ideas of having dance lessons to prepare for dance nights out were now irrelevant. When folk were tired of dancing, there were bar spaces for chatting (although probably not so much of the latter in venues run by church organisations).

Although the Musicians Union tried to maintain older patterns in established ‘ballrooms’ – for example, briefly insisting that bands should have a minimum of 7 members (p.76) – which suggested old-time dance skills had not entirely died, modern musicians just moved into new kinds of venues, as well as continuing to play in irregular spaces as they always had done in smaller towns. The marketplace also adjusted with different kinds of dance styles and music programmed for different nights in the same venues. DJs began to emerge – one unfortunate Scot being described as ‘the Scottish Jimmy Savile’ (p.104) – with Radio Scotland emerging as a lead player in this more technologically-driven approach to music.

By the late 1960s – the years when serial killer Bible John was preying on young women dancing in The Barrowland – teenagers going to clubs in cities were part of an edgy counterculture. Art School bands were at times “too clever” to be good to dance to (p.115) although their innovations also helped to transform the scene. The dividing line between dance club and rock concert was, in the Scottish context, very thin. But as music to dance to separated from music to listen to, the day of the old style dance hall was over. In the words of this history, “the 1970s: as live acts explored music you couldn’t dance to , the DJs record decks became the main source of moving sounds – with help from better speaker systems” (p.124). The disco had arrived, with venues such as the Electric Garden catering for this new incarnation of glitter-ball ceilidh.

The broadly chronological arrangement of chapters allows the anecdotes to dot around many different small town and larger city venues, rather like an increasingly busy road trip. Everywhere has its own loved places, and local musicians, which crowd the pages in both image and text.

Many Scots owe their very existence to the fact that their maw once said ‘aye’ when posed the question on the title page. However, that is pretty much the only role for women in the world presented by this history. Overwhelmingly, the images in this book are of young male musicians: many of them, with other day jobs, using ‘being in a band’ as an extension of what I might describe as traditionally single-sex Scottish forms of male homosociality. I only noticed female musicians at p.117 and then, in a picture of an unnamed band. Scottish women are there as fans, as fashion followers, sometimes as hostesses and bartenders, or as customers – ‘yer maw’ – but not as musicians; the exception, Loulou, is mentioned once in dispatches if not in the index. I’ve no doubt this is pretty accurate; but it does suggest Scottish women needed to work harder than in some other national cultures to get on stage as performers rather than as groupies. This is indeed history: but perhaps not simply the “good old days”.

Further Reading

- Kate Molleson (ed.), Dear Green Sounds: Glasgow’s Music through Time and Buildings (Glasgow: Waverley Books, 2015)

- Eddie Tobin with Martin Kielty, Are Ye Dancin’? The Story of Scotland’s dance halls, rock’n’roll, and how yer da met yer maw (Glasgow: Waverley Books, 2010)

- “Waverley Books”, in Publishing Scotland

- “I crawled to the phone. The pain was awful . . . it was like a red-hot poker”: EXCLUSIVE: Eddie Tobin, the leading entertainment industry figure shot in his home on Wednesday night, is recovering from his wounds in hospital in East Kilbride”, in The Herald Scotland, 14th October 2006