The story of the Scottish Reformation and its music is here brought into focus by the biography of Jhone (John) Angus (c.1515-c1596). Before 1560, Jhone Angus was precentor and in charge of music in Dunfermline’s Benedictine Abbey. After 1560, the Scottish Reformation had no use for Abbeys or their music. Yet most of what Angus composed is known from works that appeared in the 1560s, after the Reformation. Why?

A 21st Century Project – just in time….

The authors of this book are leading experts on this period and its cultural and religious history. Jamie Reid-Baxter (currently at the University of Glasgow) has long been a powerhouse of expertise on the world of 16th century Scotland and a charismatic advocate for its music. Michael Lynch held a named chair in History at the University of Edinburgh. E Patricia Dennison edited books for Historic Scotland ‘Historic Burghs’ 3rd series, including (with Simon Stronach) Historic Dunfermline: Archaeology and Development (2007. The 5th section of the book, which specifically discusses, Angus’s music was informed by the painstaking research of the late Kenneth Elliot, who was also present at a concert given in 2010 in Culross of Angus’s music.

Sometimes smaller presses and community projects produce books of national importance which would be the envy of many much larger publishers. This is such a book, organised to mark the 450th anniversary of the Scottish Reformation (well, from 1560 to 2011 is 451 years, but close enough!) The website of the Dunfermline Heritage Community Project that produced this book still lives on, with last entries around 2014, but the project group itself is no longer operating, which creates an interesting parallel case to the project-lifecycle of the Wode psalter, the 16th century collection in which the music discussed here was first recorded.

Other aspects of the project also tell a story of changing civic culture. Town archives in Fife have been moved from localities to a central Fife facility in Glenrothes, in the case of Dunfermline, leaving the Dunfermline Carnegie Library in September 2012. While public money curation probably made this essential, and the Fife Archive reading room looks to be well equipped and welcoming to visitors (see their website for opening times), arguably the centralisation also made it a bit more difficult for volunteers to access this material. This book emerged from a period where local folk with antiquarian interests were still the prime cataloguers and curators of this material alongside professional academics. The Fife archive has a more professionalised staff, which is good, although its search engine doesn’t go back before 1800, which suggests this earlier material may be in less accessible holdings.

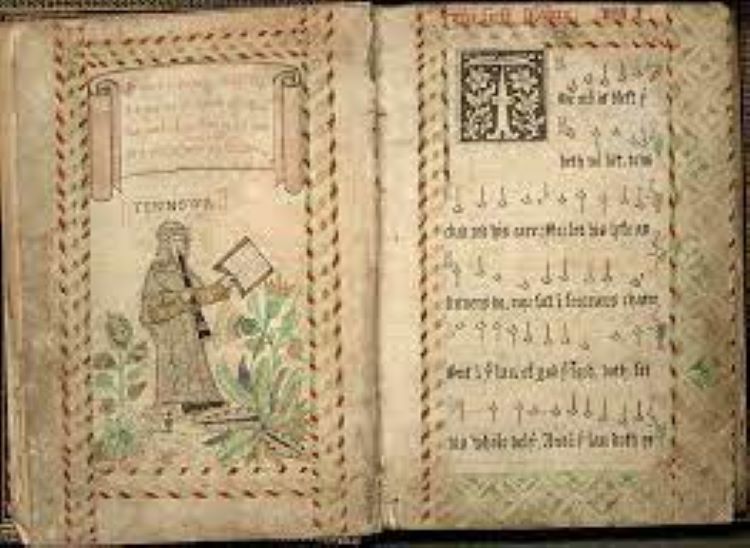

A couple of decades back from today, the granular local history work summarised in the Scottish Burgh Studies fed many lively tributaries into the larger river of the national narrative, and the Dunfermline study was driven partly by the energy of local volunteers: probably this was an important seed ground for this beautifully illustrated hardback celebration of local monk and man of music, John (Jhone) Angus). The other clear inspiration was the work carried out around the same time by Edinburgh University academic Jane Dawson and her colleagues, on the Wode Psalter, produced in 16th century St Andrews at the other end of the long kingdom of Fife. Jhone Angus’s music can be found in that manuscript collection, and illustrations from the Wode partbooks feature generously in this book.

Dunfermline: a royal capital and its music, before and after 1560

Dunfermline was chosen to be Malcolm III’s royal seat in the 12th century (the ballad of “Sir Patrick Spens” opens with the king sipping bluid-red wine in his tower in the city) and in the 16th century was still a very significant town, with a huge complex around the 11th century Benedictine Abbey which, before 1560, was St Margaret’s shrine and a major site of pilgrimage. Today the extant parts of the monastery complex remain a site of worship run by the Church of Scotland. The Scottish Reformation did away with monasteries and shrines and rapidly transformed Dunfermline’s place in cultural geography.

Chapter 1 of this book summarises the turbulent politics of Scotland before 1560. Chapter 2 looks at the impact of the Reformation on Dunfermline and its Abbey. There was no local grandee who was particularly hot for reform: for townspeople, the Abbey was, importantly, also host to their parish church: “contemporary records make it clear that the townspeople held their parish church in great affection” (p,14). However, under the leadership of a new Protestant minister (David Ferguson, a glover from Dundee) and with the compliance of local families (particularly Robert Pitcairn, a layman who was appointed as the abbey’s commendator or administrator in 1561) the nature of worship was transformed. The former monks – including Jhone Angus – were allowed to continue to live in the town, and even received life-pensions (p.18) so long as they did not challenge the new order: they could even serve as “readers” in parish churches in the area (p.20).

Jhone Angus thus found himself living in the vicarage of Inverkeithing parish in 1562 from which place he presumably continued to give some level of ministry service to local parishioners. Chapter 3 thinks about what kind of music happened in this kind of local parish before 1560. This would have been rather more modest than in the Abbey, although before 1560, liturgically rich with chant sung by the clergy: the Mass, and the daily Office of the Hours sung in Benedictine establishments (helpfully summarised for readers not familiar with these services and their music).

Chapter 4 discusses the new Protestant music. This was sung by all the congregation: Scottish adoption of Genevan psalmody helped to ‘build a northern Geneva’ (p.34) using the unison material contained in the authorised Whole Booke of Psalms (1562). However, this first decade was exploratory, and in the university town of St Andrews, Mary Queen of Scots’ half-brother James Stewart commissioned a psalter project to set the new vernacular texts in 4-part harmony. It is here suggested that David Peebles, the main composer in this project, ‘remained at heart a Catholic’ (p.36) and hence dragged his heels; Stewart turned to Thomas Wode who was rather more enthusiastic. Wode, also a former monk, and soon-to-be minister in charge at Holy Trinity St Andrews, seized the thistle and his name eventually became synonymous with the project. Without Wode and his partbooks, the music of Angus, and of his contemporaries David Peebles and Andro Blackhall, would have been lost irrevocably. Wode was a skilled copyist, part of generation whose skillset would not be readily replaced after 1560, despite the revival of former song schules under burgh management in 1579. As music literacy waned, so did new composition: Scottish music did not begin to recover from this infrastructure collapse until the later 17th century.

Chapter 5 is where we finally arrive at the specifics of Jhone Angus’s. Working from the relative desert of Inverkeithing, in the mid- to late-1560s Angus composed canticles for Thomas Wode’s project, using new Scots translations from various sources but particularly the 1562 Whole Booke of Psalmes. Wode was also appointed to be a canon in the Chapel Royal prebendary of Kirkynner and Kirkcowane, which may have given him a space where more elaborate music was possible. The Chapel Royal was part of the personal apparatus of the monarch – in this case, James VI. Canons such as Angus who also had local residencies may not have given daily service to the King, but were available if needed, and their higher-level level of musical skill reflects their possible value to the court’s music.

Angus particularly contributed settings of “Canticles”. “Canticles” are Biblical texts that are presented as having originally been delivered as song, often as praise and moments of celebration: for example, the Song of Mary (Magnificat) from Luke 1:46-55. More loosely, the Lord’s Prayer and the Creed as communal moments of shared doctrine may also be sung. As Protestants believed that only scriptural texts should feature in worship, these spiritual songs were a core part of the new Protestant music alongside the 150 psalms from the Old Testament. Canticles feature particularly in Morning and Evening prayer in Reformed worship, and one suggestion in this book is that Angus’s canticle settings in the Wode partbooks might have been intended to encourage congregational singing of these texts alongside and in addition to Psalms in these particular services (p.49).

Angus’s canticle settings use the syllabic homophonic 4-part harmonic style that Stewart set as standard for the Psalms in the Wode collection, and which may have disheartened Peebles whose style had been more polyphonic before 1560. A helpful list on p.49 notes all the canticles in Wode notes which were probably contributed by Angus, and detailed notes track the probable originals of the vernacular texts. Biographical information is also provided for Andrew Blackhall of Musselburgh (pp.50-52) whose career as a former monk in the Reformed church was rather more successful than Angus’s, and Andro Kemp who ran the song school at St Andrews.

Marginalia in the Wode psalters makes it clear that Wode thought Angus was a higher-order musician: ‘guid’ and ‘meike’. The singing on the accompanying CD performed by James Hutchinson’s “Sang Schule” group is certainly easy on the ears: sweetly precise and careful in using period pronunciation of 16th century Scots, they demonstrate that this material can be elegant as well as textually clear.

The conditions that allowed local and national expertise to produce a book like this have changed beyond all recognition in the past 15 years: a book AND a CD – both technologies that have given way to cheaper, more ephemeral forms of web-based dissemination (thank you to the Church Service Society who have recently determined to continue hosting the Wode psalter music on their website). As we see from 16th century Scotland, cultural change can happen at bewildering speed. I look back at the lost world a partnership of local and national contributors could produce this book, and marvel.

Further Reading and Listening

- Jhone Angus and the Wode Psalter – Church Service Society

- Jamie Reid-Baxter, Michael Lynch and E. Patricia Dennison, Jhone Angus: Monk of Dunfermline & Scottish Reformation Music (Dunfermline: Dunfermline Heritage Community Projects, 2011) and CD distributed to accompany the above – James Hutcheson dir. Sang Schule (Edinburgh: Sean Williams, Double Bridge Press, 2011)

- Elizabeth Patricia Dennison, Simon Stronach, Historic Dunfermline: Archaeology and Development, from The Scottish Burgh Survey (Dunfermline Burgh Survey, 2007)

- Dunfermline Heritage Community Projects (DHCP) website (archived)

- Fife Archives Searchroom

- Sang Schule : Scottish Vocal Group specialising in early music, founded in 2000, and occasionally refounded since then

A very interesting post- good to be reminded of this very worthwhile project.

Thanks James – I’m going to do at least one of the Angus canticles in May, so I’ll wave it about there as well. If you are around you’re welcome to come and have a sing. See Events in the Laidlaw Music Centre’s brochure for next spring – Study and Sing day.