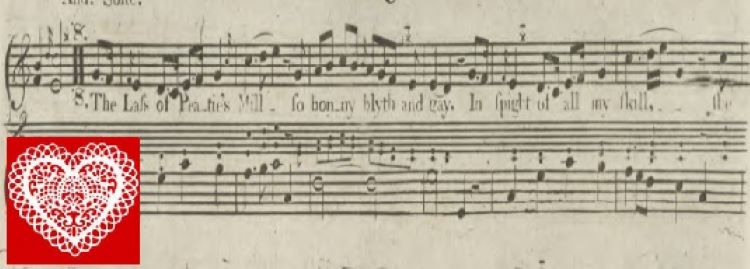

Image: “The Lass of Pattie’s Mill”, lyrics by Allan Ramsay, arranged by Dominico Corri, from his “A New & Complete Collection of the Most Favourite Scots Songs” (London, c1790-1801), p.69

The Corris (that’s Corri, not Corrie) have been catching Soundyngs attention, as another interesting example of not-necessarily-native-born musicians and musical entrepreneurs whose activity in Scotland significantly impacted on aspects of Scottish musical life. This post also connects with the unlikely finding that a reliquary containing the bones of St Valentine currently abides in the church of Blessed St John Duns Scotus in Glasgow – another outsider to settle in Scotland, albeit one who arrived posthumously and not entirely verifiably, and not related to the Corris, but timely for this week. To all lovers, here’s a post about the musical Corri family, who came to Scotland from that most romantic of all European countries, Italy.

The Corri family were originally from Rome, but came to the British isles and in London, Edinburgh and eventually Dublin, made a mark on 18th and early 19th century musical life. Domenico Corri (b.1746) composed music for voice, violin, and harpsichord, and had an enthusiastic if not always financially wise enthusiasm for musical entrepreneurial enterprises. In his youth, according to his later memoires, he lived in the court-in-exile of Charles Edward Stuart, who had made his home in Rome after the defeat of Culloden. The expatriate community who heard Corri and his wife perform in Rome included Charles Burney, who wrote admiringly to others in the British Isles in particular of his admiration for the voice of Signora Corri (also known as ‘La Miniatrice’) (Tinagli, 1999, p.140-45). Inspired, perhaps, by the Bonnie Prince’s tales of his lost homeland, but doubtless also lured by the promise of regular work, Corri came in 1771 to Edinburgh with his opera-singing wife in response to an invitation from the Edinburgh Musical Society, and for 18 years was active in concerts in the city. He also attempted, unsuccessfully, to make a profit from running the Edinburgh Theatre Royal, which unfortunately temporarily rendered him bankrupt (Ward Jones et all, 2001).

Undeterred, in 1785 Domenico went into partnership with his younger brother Natale (b. 1765), a singer and guitarist, starting up a music publishing business. For a decade, this produced a fair amount of Scots-Italian music including some composed by Domenico himself. Typically, these took the form of Scottish melodies harmonised and accompanied by instruments fashionable in Italian art music. Most settings use the melody plus figured bass technique that was a late hang-over from the earlier baroque practice. The business was initially fronted by Domenico’s son, John Corri, as the father’s theatrical bankruptcy disqualified him for a time; however, the brothers also worked with a local partner, James Sutherland, until Sutherland’s death in 1790 (Farmer, p.295).

Publications by Dominico Corri appearing during his time in Edinburgh include:

- A Select Collection of the Most Admired Songs, Duetts, Etc from Operas in the highest esteem, and from other Works, in Italian, English, French, Scotch, Irish Etc (c1779) (3 volumes). Scottish material is particularly concentrated in volume 3, and presents examples of how continental figured bass was still relevant to chamber music performance.

- A Musical Grammar (Edinburgh, 1787) again, includes notes on realising figured bass to accompany melodies.

- A New & Complete Collection of the Most Favourite Scots Songs: including a few English & Irish (Edinburgh: Corri & Co). The National Library of Scotland has a digital copy available.

- (with Natale) A Select Collection of 40 of the most Favorite Scots Songs also sometimes listed as “Forty Scottish Songs” (multiple editions)

In the year that Sutherland died, Domenico moved to London and set up business there afresh in partnership with Dussek. Natale, however, stayed north. Corri & Co (Edinburgh) benefited from the 2-city family connections, and expanded its catalogue of music composed for songs and increasingly the pianoforte. Two shops opened on North Bridge Street and South Street (Farmer, p.295), suggesting sales of sheet music to an expanding city clientele was brisk or at least optimistic.

As the Edinburgh Musical Society ran down and eventually closed its doors in the 1790s under the pressure of its operating debts, Natale Corri established concert rooms and a regular winter series of recitals, at which ticket-paying audiences could hear the latest music and feel themselves to be part of a European fashionable mainstream. The mid-1790s briefly saw bankruptcy once again, but this resilient family relaunched and continued to sell music and run concerts in Edinburgh until 1821,when Natale (now in his mid 50s) left Scotland to return home to Italy.

As we approach 14th February and Valentine’s Day 2024 (also, this year, Ash Wednesday, but for this blog, let’s keep the music flowing…), we might think, how did people celebrate this festival of love with music in the past?

The Caledonian Mercury reported that for Valentine’s Day 1800, the Corri family offered a public recital to the citizens of Edinburgh. Possibly, the citizens might not have fully recognised the significance of that date (did Presbyterians celebrate St Valentine?) The Catholic Corris, however, must have had some inkling. The newspaper advert announced that Mr and Mrs Corri “respectfully informed their Friends and the Public”, that “their Concert is fixed for Friday the 14th February 1800 “ in the Assembly Rooms, George Street. The programme on this occasion was select works from Handel “on the plan of an Oratorio”. Tea and coffee was included in the ticket price. This was all wholesome stuff: scripture and tea, a Hanoverian composer… no sense of overtly Roman Catholic festivity … what could possibly be objected to … (Caledonian Mercury, Saturday 8 February 1800, p.4).

The University of Glasgow’s Burns for the 21st Century project also has a nice blogpost about an imagined 18th century singing lesson, as it might have been shaped by Corri’s ideas on singing as laid out in his treatise, The Singer’s Preceptor (1810) (see Further Reading, Brianna Robertson-Kirkland). If music and song be the food of love, play and sing on…

Further Reading

- Anon, ‘Assembly Rooms, George Street”, Caledonian Mercury, Saturday 8 February 1800, British Newspaper Archive

- Sonia Tinagli Baxter, Italian Music and Musicians in Edinburgh c.1720-1800: A Historical and Critical Study, PhD Dissertation, University of Glasgow, 1999.

- Domenico Corri, The Singer’s Preceptor (London: Chappell & Co, c1810) – preface material in some but not all editions includes the ‘Life of Corri’.

- Henry George Farmer, A History of Music in Scotland (London: Hinrichsen, 1947), p.295

- Peter Ward Jones, rev. Rachel E Cowgill, J Bunker Clark, and Nathan Buckner, ‘Corri Family’, Grove Music Online, 2001; Accessed 9 Feb. 2024.

- Peter Ward Jones, rev. Rachel E Cowgill, ‘Corri, Natale’, Grove Music Online, 2001; Accessed 9 February, 2024.

- Paul J Revitt, ‘Domenico Corri’s “New System” for Reading Thorough-Bass, Journal of the American Musicological Soceity 21(1), 1968, 93-98, https://doi.org/10.2307/830388

- Brianna E Robertson-Kirkland, ‘An 18th Singing Lesson in Scotland’, Editing Burns for the 21st Century (University of Glasgow), Accessed 12th February 2024

- and here for the 14 February 2023 STV report on St Valentine’s Bones in Glasgow

Also – for those interested in ground bass music in 18th century Scotland, check in with the BassCulture project. This AHRC funded research project (ending in 2016) involved researchers from the Universities of Glasgow and Cambridge, and the Scottish Conservatoire, who looked at indigenous use of bass lines in Scottish music, and suggests that practice wasn’t simply driven by Italian style. Their outputs include the Historical Music of Scotland website and database.