Featured image: The Battle of Camperdown October 1797, by Thomas WhitcombeRoyal Museums Greenwich catalogue CC-BY-NC-SA-3.0 license

A new EP release by Concerto Caledonia of Pietro Urbani’s frankly slightly bonkers cantata, ‘The Ever-Memorable Battle of Bannockburn’ (Edinburgh, 1797), prompts an excursion to the late 1790s to consider what impact the French military wars had on Scottish musical tastes, and how music composition in that particular year might have been heard in a period of national crisis. This post wonders whether this odd piece of music – which aroused laughter from modern audiences that is clearly audible on the Concerto Caledonia live recording – was an intervention in a 1797 debate in Scotland about the meaning of liberty at a moment of national military crisis. It is very difficult to know what the affect of historical music might have been on its original audiences, but re-imagining the historical context of this piece’s original point of composition makes it possible that what we hear as somewhat ludicrous (if, in this release, also entertaining and finely performed) might have been very carefully balancing an ambiguous mixture of patriotic pride and topical anxiety for its original Edinburgh audiences.

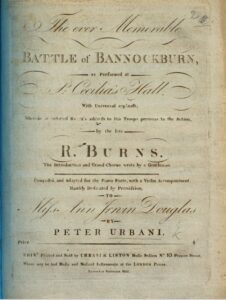

Above: Title page of The Ever Memorable Battle of Bannockburn (Edinburgh: Urbani and Liston, 1797)

Pietro Urbani was an Italian tenor and composer, who settled for some years in Scotland, performing regularly in Edinburgh and Glasgow, and taking an interest in arranging and publishing collections of Scottish songs. These he sold from his shop and print shop in Princes Street, run in partnership with Edward Liston from 1995 (see Johnson). He also had business and personal connections with Dublin, and eventually died there in a state of poverty in 1816. Letters from Robert Burns to Alexander Cunningham in November 1793 (Roy II, p.258) show discussion between Burns and Urbani took place when they meet in Dumfries that summer, probably including Burn’s lyric ‘Scots Wha Hae’ which Burns envisaged being sung to the traditional Jacobite tune ‘Hey Tutti Taiti’ (Crawford, p.368). This song, which recreates Robert the Bruce’s speech rallying his troops on the eve of Bannockburn, lies at the heart of ‘The Ever-Memorable Battle’, but is sung to rather different music newly composed by Urbani in a pastiche musical style that combines Italian heroic opera with the odd gesture to Scottish dotted rhythms.

The political situation in summer 1793 was rather different from 1797. In 1793, Burns was aware of local Jacobite sentiment circulating in Dumfriesshire, and was probably sympathetic to some aspects of radical politics, despite his employment as an Exciseman (Crawford, p.379). Burns died in July 1996; by the time that lines from his poem featured in Urbani’s ‘Ever-Memorable Battle’ cantata, it would have been without any personal endorsement from the poet. Indeed, the letter to Cunningham mentioned above suggested that the two men fell out over what had been discussed or agreed in summer 1793. However, Urbani’s decision to compose a multi-sectional musical narrative about the battle suggests a curiously unstable sense of national identity experienced in the year following Burns’s death.

The lyrics from Urbani’s ‘Battle’ – with the start of Burn’s lines in italics – are quoted below from the first edition printed for voice and piano.

Recitative: Of all the Battles which in former days

Added to Caledonia’s warlike praise

None e’er so bold, so rout e’er so complete,

As when at Bannockburn the hosts did meet.

No day so fatal to the English name

So prosperous none to Scottish freedom’s flame

Proud Edwards’s hosts came on in fierce array

While Bruce addressed his troops, and thus did say:

(the music for this is in the style of Handelian heroic opera, which David McGuinness of Concerto Caledonia has arranged for a small string group and fortepiano).

Aria: Scots wha hae wi’ Wallace bled etc (words by Burns, music by Urbani continuing in the heroic Handelian style)

Following this solo section, the piano alone presents the audience with sections of instrumental music representing different phases of the battle, with descriptive tags in the score explaining the unfolding drama. In Concerto Caledonia’s recording, these are declaimed by a narrator, to faintly grim laughter from the 2009 audience: the Scots army kneeling to pray before advancing; the order being given for battle; the two armies advancing; the English falling down in to Halberts Bog; close action with sword; trumpets and horn signals for a cavalry charge; the ‘total rout of the English army’; lamentation of the wounded; victory announced for the Scots. After this historical account, the narrative fast-forwards to the imagined present moment, with a final chorus scored for SAB to these words, written ‘by a gentleman’ (i.e. not Burns):

May Scotia’s sons, as Bruce be free

And always hail sweet Liberty!

As Britons still more happy be,

By freedom guarded and the sea.

This final chorus, with its insisting AAAA rhyme-scheme, collapses the historic enmity into a joint alliance, still in defence of liberty, but now acting, as Britons, all together against an enemy over the seas. 1797 is not 1793.

The French Revolutionary Wars of 1792-1802 impacted on many different national European musics, from the popular revolutionary songs of the French themselves, to occasional music. British naval prowess was critically important to its successes against the French, as was recognised internationally by Haydn’s triumphalist Nelson Mass and arguably the militaristic music of Haydn’s Te Deum in C dedicated to the Empress Maria Therèse, both performed in 1800 in Esterhazy for the diplomatic visit to Austria by the famous English Admiral and then recent victor of the Battle of the Nile. Scotland’s involvement in sea as well as land action has been described by Sara Caputo; this music would seem to speak to Edinburgh pride in this recent phenomenon.

The depiction of historic warrior culture in Scottish poetry and music of the period has a curious Janus-faced ability both to celebrate Scottish patriotic identity located in the wars fought against the English, and also to position pride in this historical Scottish bravery as a critical part of the modern British Isles defence of liberty. To date, there isn’t a single survey of Scottish music inspired by this, although there may well be genre-specific studies on British ballads and even bagpipe military music. The changing course of events over the decade must have invited a range of fluid responses across different genres and for different audiences, including attention to the changing nature of warfare.

There is quite a bit of historical writing on the 1790s describing the profound shift in Scottish involvement in the British armed forces and the consequences of this for patriotic affiliation (see Caputo and Cookson). Military recruitment, including in the Highlands for the first time since the Jacobite period, provided many landowning families with Jacobite histories an opportunity for political reinstatement, but initially encountered less than universal enthusiasm amongst potential recruits. In 1797, there was widespread unrest in various areas throughout Scotland to the 1797 Militia Act including protests and disturbances in Aberdeen, Fife, West Lothian, Stirling, Lanarkshire, Dunbartonshire, Kirkudbright, Ayrshire and Perthshire, and a massacre of civilian forces by the regular army in Tranent on 19th August (see Logue and Western).

In 1797, British naval forces were successful in battle despite difficult odds. February of that year had seen a British naval victory against the Spanish at Cape Saint Vincent. October saw the battle of Camperdown in the North Sea, between the British navy and the French-backed Batavian Republic; Dundonian Admiral Adam Duncan won the day, and today, Dundee city’s Camperdown Park recalls this victory and Duncan’s elevation as Viscount Duncan of Camperdown. Domestically, there was less happy news. French forces briefly managed to invade near Fishguard, in Wales, drawing attention to the need for locally-based defence forces. Discussion grew about the desirability of forming a Scottish Militia: a government Act to this end was passed in June. However, navy mutinies (the Spithead and North Rebellion) and popular unrest in late summer against enforced militia recruitment showed that the lower classes were far from convinced that their own personal ideas of liberty were well-aligned with the interests of the state. The international situation worsened when in October of that year, the coalition of European forces fighting Napoleon was broken apart by the Treaty of Del Campo, leaving the British as the sole nation still openly at war against France and its allies. All in all, this was a crisis year, and a watershed moment for the Scots involvement in British defence.

Urbani’s cantata, therefore, was composed, performed and published at a period of international and domestic crisis, and its belligerence needs to be thought about in the febrile anxious months when Britain stood alone against Napoleon and when domestic resolve in the face of this danger was uncertain. It might have been heard, in Edinburgh’s St Cecilia’s hall, as a call to arms.

Karen McAulay’s research project ‘Saved from Stationers Hall’ investigated what music was acquired by the University of St Andrews library in the period it had copyright library status and therefore the right, not always fully pursued, to request any new book published from British publishers. Surveying what actually was acquired gives an insight into the interests of users at the time. McAulay’s book-length study of this and other aspects of music publishing in the period is in preparation, but it was my privilege to help her to sing some of this material in the early days of the project. Sheet music from the 1790s held in the University of St Andrews Library Special Collections shows the University bought and bound up several voice and piano (or harp) drawing room songs produced using fine italic type on topics of British patriotic pride, for example, the ballad below satirising the Spanish, French and Batavian losers in 1797 naval battles. The lyrics of ‘French Fraternity’ ‘by a lady’ talk about ‘Britannia’ fighting treachery and praises three British admirals – Howe, who had quelled the Spithead mutiny in 1797; John Jervis St Vincent, who had triumphed against the Spanish at the 1797 Battle of Cape Vincent, hence his title; and Duncan, of Camperdown. The song therefore must date from around the period of Urbani’s cantata, and shows – at least in St Andrews – that staff and students were interested in celebrating this moment by ordering this music up from London.

“The faithless Monsieurs have long labour’d in vain

Britannia to brave on her own native main;

Now with treacherous freedom they bribe and betray

And Don and Mynheer they have forced to the fray

With the hugging so hard of fraternity pure

Of Monsieur and Ynher, Don Myheer and Monsieur,

All leagued to give Britain at once her death blowk

All beat by brave Duncan St Vincent and How.

…

Now banished by force from our free British Isles

They strive to subdue us by Jacobine Wiles;

Puffed Braggarts of Freedom! O Britans [sic] beware

That moment ye Flinch ye are crush’d in the Snare.

With the hugging so hard etc”. (p.2-3)

The refrain’s barely contained dig at the implied homosexual embrace of these foreign enemies shows how heteronormative representations were reinforcing ideas of British patriot identity. The involvement of women either as dedicatee or composer in both the works discussed here shows how this was implicated in the identity politics of the period: Urbani’s piece is dedicated to a Miss Ann Irvin Douglas, while the ‘French Fraternity’ is by an anonymous ‘Lady’.

It would be very interesting to have a research project that looked at the impact of the Napoleonic wars more widely on Scottish music of the period, including wider attention to cheap ballads of the period alongside the drawing room music discussed here. McAulay’s forthcoming book may well supply this. Music has curious strength in arousing emotion and directing towards objects of affiliation. In the case of Urbani’s Battle of Bannockburn, heroic music may be attempting to smooth a way for Scots to reconcile their historic patriotic pride with British state policy, in the embattled year of 1797: to facilitate shared action by all in Britain in the face of a new common enemy.

Listen to:

- Concerto Caledonia, Late Night Extras including track 1 James Gilchrist, Michael Marra, ‘The Ever Memorable Battle of Bannockburn’, arr. David McGuinness (June 30, 2023) , track 1 recorded live in The Hub, Castlehill, Edinburgh 2009 by Steve Portnoi.

Further Reading

- Anon (‘A Lady’), “French Fraternity” (London, T Skillern, s.d.) bound with other music of the period in University of St Andrews Special Collections catalogue sM1.A4M6v40

- Sara Caputo, ‘Scotland, Scottishness, British Integration and the Royal Navy, 1793-1815’, in The Scottish Historical Review 97(1), (2018), 85-118

- E. Cookson, ‘The Napoleonic Wars, Military Scotland and Tory Highlandism in the Early Nineteenth Century’, in The Scottish Historical Review, 78(205), (1999), 60-75

- Robert Crawford, The Bard: Robert Burns, A Biography (Pimlico, 2010)

- David Johnson, “Urbani, Peter.” Grove Music Online, 2001; Accessed 30 Jun. 2023

- Kenneth J Logue, ‘The Tranent Militia Riot of 1797’, Transactions of East Lothian Antiquarian and Field Naturalists Society, 14 (1974), 37-61

- Karen McAulay, ‘Saved from Stationers Hall‘, Special Collections Blog from University of St Andrews Library (August 2016)

- Eric Niderost, ‘Scottish Highlanders at Waterloo’, Military Heritage 13(5), (2012), 23-31

- G Ross Roy and J de Lancey Ferguson (editors), The Letters of Robert Burns II. 1790-1796. (Oxford University Press, 1985)

- Pietro Urbani, The Ever Memorable Battle of Bannockburn, as performed at St Cecilia’s Hall with universal applause, wherein is inferred Bruce’s address to his troops previous to the Action by the late R Burns (Edinburgh: Urbani and Liston, 1797)

- J R Western, ‘The Formation of the Scottish Militia in 1797’, in The Scottish Historical Review 34(117), (1955), 1-18