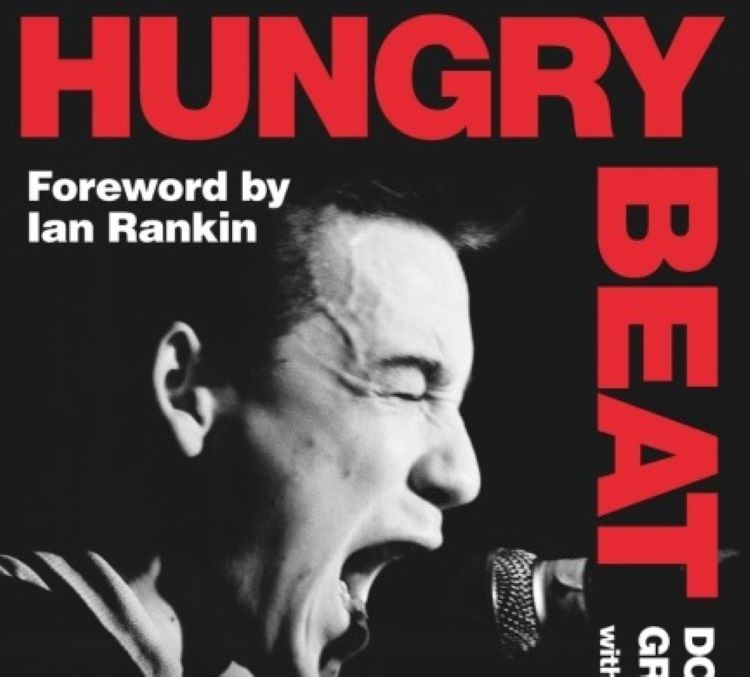

- Douglas Macintyre, Grant McPhee, with Neil Cooper, and a forward by Ian Rankin, Hungry Beat: The Scottish Independent Pop Underground Movement (1977-1984). (London: White Rabbit, 2022)

Hungry Beat is a behemoth of a book that, since it spans exactly the years of my high school grappling with pop music, has been a personal summer must-read. Ian Rankin’s foreword to this book asserts “every town seemed to have a band in the late 1970s and early 1980s” (p.xiii). Indeed yes. Even if that band was a bit ropey, my memory of small town Highland garage bands of that period is that there was usually one performer who, in a bigger place, at least in his or her head, could have been a big(ger) star. Playing in a band was a rite of passage, a coming of age. We all understood there was a hierarchy: from the school disco guest spot (for Rankin, the YWCA hall in Cowdenbeath and a ‘busload of kids with special needs’) to local heroes in a regional context (Rankin’s Dunfermline neighbours, The Skids), and from there, dreams of platinum discs. Hungry for fame – but also, for many of the bands and artists discussed, hungry in other ways, because Scotland in these years was not a rich place.

‘Independent’ in the context of this book refers to bands that were emerging outside of the big record label framework. This book is an oral and photographic history of the people, bands and music involved in the rise and fall of two particular independent labels, Fast Product and Postcard, using interviews and in the words of those who lived through it. This book tries to capture the flavour of a period of Scottish popular music when breaking the hold of the big labels and promoters south of the border, and indeed moving into their territory, seemed possible. Reading this book in the light of the last 4 decades of Scottish politics, it is easy to imagine – although not explicitly suggested – that searching for such independence in music making and production had a synergy with wider period politics. As John Purser has said, the story of these initiatives reveals the relative weakness of the Scottish music industry, which worked in the shadow of southern sector leaders (Purser, 325-8).

The writing team brings a useful blend of talents to the project. Grant McPhee, is a film-maker and his documentary film made for the Edinburgh Film Festival (Big Gold Dream, 2015) is well-worth watching to get a grasp of the economically run-down state of Scotland in the late 1970s and the character and actual sound of the musicians’ voices active at the time. Douglas MacIntyre, McPhee’s co-author, ran his own independent label, The Creeping Bent Organisation, in the 1990s, which gives him insider insight into the workings of the industry. The third collaborator, Neil Cooper, is a music journalist, and his contacts and writing experience help to add flesh to the material gathered. The result is like being in a book room listening to a lot of interesting people talking together about the best and worst of times: Campbell Owens of band Aztec Camera, described his home-town of East Kilbride’s relationship with punk as being the obvious response to the bleakness of post-industrial Scotland; but the creative response to this bleakness was, from this band and others, some startlingly interesting and intelligent music (p.208).

The list of bands cited includes voices from many of the best-known bands of the period, from Aztec Camera and Altered Image to the Rezillos and The Bluebells. While Scottish bands lie at the heart of the story, we also hear about English bands such as the Mekons and The Human League, who worked with these independent Scottish music entrepreneurs, placing the Scottish activity in the wider context of British art-college derived music-making. English bands played the part in helping to leverage the Scottish labels into the wider marketplace; but larger established companies are also a constant pressure, luring the most successful groups to larger label signings in London, Manchester or Liverpool.

The explosion of independent band culture in this period is explained to be a combination of:

- The impact of punk rock, which kicked to one side pop’s glossy gatekeeping devices and indeed the need for any kind of aesthetic refinement or expensive presentation. As Rankin puts it, “Punk had taught a whole generation of home-grown fixers and entrepreneurs that you could keep things local. London needed you. You didn’t necessarily need London.” (p.xvi). Ground zero of the book is the impact on Edinburgh music fans of punk rock band The Clash, whose “White Riot” tour concert in the city in 1977 is presented as game-changing. English-punk support acts Subway Sect and the Slits (the latter an all-female punk band) were raw, rough and clever, and showed how big-impact music could be done on the cheap by DIY artists.

- “Record shops were the epicentre of most local music scenes in towns throughout Scotland” (p.17). Retail record store notice boards were covered with personal ads – ‘band looking for’ notices – which helped many a local band to form up from rough initial jamming sessions, or to meet huddled over a bin of music signifying a shared interest. Record shops were gathering places before the internet curated our tastes into algorithmically defined silos and remote asynchronous engagement.

- Cheap print and copying technology that facilitated the creation of fan-base-building fanzines, circumventing the heavy weight music journalism of the period with local and/or niche alternative communication channels before digital social media. Independent labels also became slick in using art-college promotion methods: “Bob Last [of Fast Product] would release small works of art, little posters in cellophane bags … we would generate work where we would cut images, slogans out of magazines, anything that we saw that caught our eye” (p.53).

- The role of radio in promoting new music, especially of innovative programming DJs working in national radio like John Peel of Radio 1, who was particularly open to listening to and giving air space to emerging bands.

- And finally, emerging cheap new keyboard synthesizer technologies, and studio experimentation, which allowed bands like Fire Engines to expand the sound of Scottish post-punk beyond the core guitar and drum line-up of traditional rock and punk (p.270).

The book looks first at Edinburgh-based label Fast Product, launched by Bob Last, Hilary Morrison and Tim Pearce in 1977, which combined low-cost, inventive entrepreneurial music-management with what MacIntyre calls ‘art movement’ aesthetics. Fast Product started off by signing English bands, getting noticed by NME, and on the back of that success, were able to develop a stable of Scottish newcomers like The Scars, The Flowers, and Fire Engines who might otherwise have struggled to break through. The label pop:aural was a spin-off from this, further developing the connection between music and visual art. Some of the bands signed initially to Fast Product or pop:aural – such as The Human League – went on to international stardom, and transferred to larger companies like EMI with more developed distribution networks, which highlights the problem faced by smaller independent labels then and now: what to do when the talent you have spotted early in their career wants to get bigger.

The late 1970s and early 80s are a period when the initial shock of punk sent out waves into new musical directions. In this experimental period, an independent record label like Fast Product was in a position to help test new sounds and ways of performing, and this section of the book describes the Edinburgh flat of Fast Product’s founders as being a kind of Scottish equivalent to Andy Warhol’s Factory. There is quite a bit of discussion in the book about how these bands reacted against British conservative politics in this period, channelling angry energy into their music, as can be heard in the Human League’s track The Dignity of Labour (FAST 10) (p.96). In Bob Last’s words, “revolution and independent ideology was thick in the air throughout 1979, as was the notion that decentralised distribution and controlling the means of production could challenge the accepted status quo of multinational corporation practice within the music industry” (p,97).

The west coast Scottish response to this, few years later, came in the form of Postcard Records and ‘The Sound of Young Scotland’. Orange Juice – a band from Strathaven – set up their own label after failing to be taken up by the big record labels (p,138). While the Edinburgh scene had diversified into post-punk new wave, Orange Juice were initially keen to keep the punk flag flying, but clearly had learnt lessons about art-based promotion. Their first single included a free postcard, and a flexi-disc with a live, low-fi recording, originally intended for a fanzine and repurposed as a marketing hook. Their first big gig was at the Glasgow School of Art (p.153) to a rowdy and less than appreciative live audience. More successful live gigs, followed. Postcard managed to dip into the Edinburgh talent by signing Edinburgh band Josef K as their second client. As in the east coast, gradually the sounds shifted to become leaner and cleaner, still guitar and drum based, but now incorporating more recognisably melodic forms of song-based music: in the words of Alan Horne of Postcard Records, ‘everything is geared towards the song’ (p.308).

What is clear is that even if Scottish independents such as Fast Product and Postcard Records didn’t always keep their talent, their presence did much to encourage emerging bands in this period to play and be heard. The members of these bands were often very young: being able to have local management options while they got established had obvious personal value to both individuals and the local musical ecology. This gave a voice to Scottish youth musicians in a critical period for modern Scottish culture and identity. If there is a major negative about the music scene, it is that men dominated to such an extent across all areas – reflections by Hilary Morrison of Fast Product, who also fronted The Flowers under the stage name of HL Ray, confirm that it was much harder for women to break through as truly independent voices: “some of the things that were said to us when we did demos were really quite disturbing and exploitative” (p289) and “as a woman, some of the shit I had to put up with was off the dial” (p.397).

Both Fast Product and Postcard Records had wound up by the mid 1980s, but today, Creative Scotland’s awards for emerging bands, which give start up studio funding, are still named after the Sound of Young Scotland with a nod to these highly creative music entrepreneurs. https://youthmusic.org.uk/node/4402

Further Resources

- Damien Love, ‘Alan Horne on the resurrection of Postcard Records’, in Uncut, 26th March 2021.

- Douglas MacIntyre, The Creeping Bent Organisation – record label on Bandcamp.

- Grant McPhee, Big Gold Dream (2015) – film.

- Grant McPhee, ‘Ain’t That Always the Way – Alan Horne After the Sound of Young Scotland 1 & the same part 2, in Penny Black Music 8th November 2022.

- John Purser, Scotland’s Music (2nd edition: Edinburgh: Mainstream, 2007), chapter 20 touches briefly on pop music since 1960.