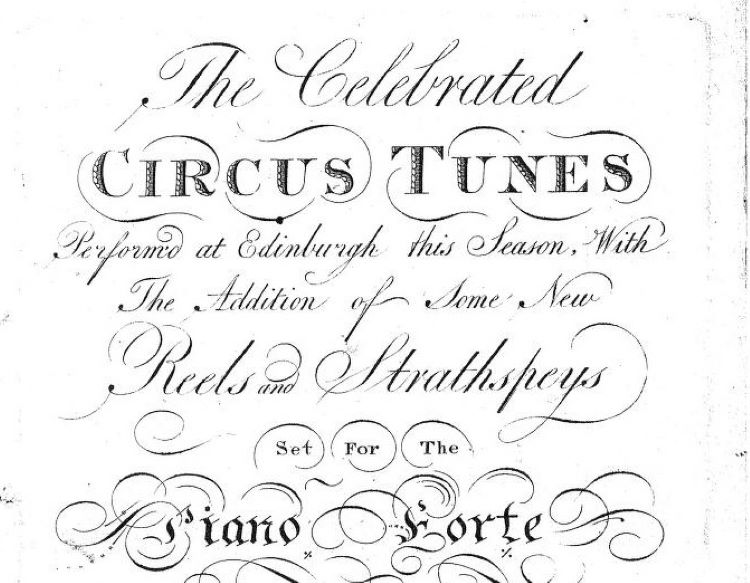

Featured Image: The Celebrated Circus Tunes Performed At Edinburgh this Season, with the Addition of Some New Reels and Strathspeys Set for the Piano Forte or Violin and Bass, by John Watlen (registered London, Stationers Hall, 1791)

For those who grew up in the days before digital on-demand printing, getting music published required a lot of risk by the publisher. Buying paper, typesetting (in music, requiring musical specialist setting and proofing), committing the presses, gearing distribution and marketing – an error at any stage could result in a pile of mouldering, unsold stock. 17th and 18th century publishers dealt with this by getting social networks to commit money prior to production by “subscribing”. Music publishing therefore depended on intense social networking, and targeting patrons and clubs who might be the first-point consumers. This leaves archival evidence in the form of subscription lists, and the essays in this collection look at what the patterns in these lists can tell us about the world of Scottish music production and consumption in the age of Enlightenment.

This book represents a number of overlapping ‘big data’ projects, which together provide a fascinating insight into the music buying habits of people of different classes and gender all over Britain (and overseas places where Britain reached, sometimes in the reprehensible context of the slave trade). London, from the earliest days of printing in the British isles, has a powerful centrifugal pull, and reading early chapters about the structures of publishing more widely can help us to understand how this might have impacted projects with either roots or impact in the north.

Of the more general chapters, Chapter 9, on the role of Music Societies, is helpful to anyone looking to understand how these provided a critical mass of purchasers for all kinds of musical activity throughout the English-speaking world: this is the context in which the Edinburgh and Aberdeen Music Societies, and their lesser satellites such as Glee Clubs, operated. The appetite for these societies, in many cities and towns, for works by popular composers such as Handel, Geminiani and Urbini sustained both regular concerts and one-off events such as benefit and commemorative programmes (p.152-176). A surprise for me was that in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, some of the best-sellers in the Music Club subscription lists are harmonised collections of psalms (p.168).

However, two chapters take us specifically to Scotland.

Chapter 5 – Simon Fleming’s discussion of subscription publishing in eighteen-century Edinburgh – reveals that Edinburgh had a surprisingly large number of women subscribers, a pattern that is quite different from consumer habits in London. It took some time for the subscription model to become established in Scotland: the late 1770s seem to be the key period. By the last decades of the 18th century, a key figure is John Watlen, whose ‘Music Warehouse’ sold all kinds of musical goods that it seems particularly appealed to women, including pianos, and music published by subscription arranged for that instrument.

This chapter reveals the business networking activity that connected Watlen with the Corris in Edinburgh, in businesses located increasingly in the new Edinburgh – Princes Street, stretching elegantly beyond the straggle of the old town, and North Bridge Street (p.79).

Focussing on a surprising anthology of ‘Circus Tunes’ (1791 and 1798), Fleming demonstrates that women, denied fully membership of bodies such as the Edinburgh Musical Society, were nevertheless allowed to access concerts and also debating meetings. They clearly responded by developing a parallel network of musical activity (p.75-6), subscribing to music publishing projects under their own names and not reliant on husbands, fathers or brothers to buy music on their behalf. An analysis of titles (Miss, Lady, Sir, Mrs, etc) reveals that 91% of subscribers to Corri’s Three Sonatas for the Piano Forte or Harpsichord (c1790) were women, marking piano-playing as a particularly feminised zone of musical activity. Some of the dance tunes in Watlen’s collections have names that point to women as particular patrons: “Miss Ann Baines Fancy”; “Lady Eliza Callander’s Favourite” etc (p.83). Others are named after less socially elevated women, who might have been circus performers. And, amongst the additional reels and strathspeys, there are even some pieces ascribed to female composers: Lady Ruthven, the Countess of Balcarres, and Miss C Dalrymple. Whatever the 1791 circus involved, which is still rather a mystery even having read this chapter, it clearly implicated a lot of women as composers, dancers, and music consumers: 77.5% of those who bought the circus collection were women (p.85). Watlen eventually – twice – went bankrupt, but his activities demonstrate that for a time at least, the female market was at the core of his operations.

The 1791 ‘circus tunes’ were padded with strathspeys and reels. The sluggishness of mid-18th century music publishing, before subscriptions really took off, perhaps explains why dance-tune compiler James Oswald left Edinburgh in the 1740s for the more lucrative entrepot of London. But by the time that the Gows were bringing out their collections of strathspeys, and Watlen his circus tunes in the 1790s and early 19th century, the market was primed for a new kind of ‘national’ music.

The other chapter in this collection with insights on the Scottish music world is chapter 10, Karen McAulay’s ‘Strathspeys, reels and national airs: a national product’ (pp.177-197). McAulay has been involved in several big-data projects – on 18th century ‘Bass’ culture and on copyright libraries – and has just sent a big book to press on Scottish music publishing in the long 19th century. Here, she initially draws on scholarship by Nancy Mace that suggests that songbooks were initially more likely to be fully registered in London’s Stationers’ Hall than books of dance tunes (1770-1820), with the former often linked to theatres and opera houses in the south, and the latter depending more on local, provincial subscription and self-publishing.

As the data presented here demonstrates, Scottish composers and publishers gradually become more assertive in the wider British marketplace. Discussion of Niel Gow’s music, edited by his son Nathaniel Gow, shows that this initially relied heavily on local subscription and no formal national registration (p.178). However, as Nathaniel began to think more about copyright protection, he began to register collections in London as well, with prefaces asserting the Gow’s compositional ownership as the Gow family’s musical reputation built steadily beyond Perthshire.

McAulay finds many subscription lists for fiddle and bass dance tunes – distinct from the piano arrangements discussed in Fleming’s earlier chapter – dominated by men, but like Fleming, notes that women were increasingly present as the piano challenged the fiddle (p.181). Once again, the names of tunes mark the influence of patrons and subscribers (p.183): the Marchioness of Tweeddale finds herself named in Gow’s third collection of strathspeys and reels. These traces are only part of the range of services the Gows performed for patrons, from teaching the children of the gentry to playing for their dances and weddings. Certain families were clearly highly influential as patrons of music and publishing: the Buccleuchs, in particular, are discussed here, but also the Eglintons, Montomeries, Grahams of Orchill, and others (p.186).

Female subscribers were evidently women of higher social status. However, in addition to the gentry, subscribers could also be music retailers or teachers of music and dance, revealing growing numbers of professional practitioners in different music business areas in Scotland. Perthshire, the homeland of the Gows and a centre more generally for fiddle playing, seems to have been well represented in subscription lists (p.187), but lists with names and hometowns for subscribers suggests that the hinterland around Dundee, Tayside, Fife and the South-East generally had a goodly scattering of music consumers involved in professions such as teaching dance (p.188-190). These kinds of subscribers were more likely to be men.

In the Gaelic marketplace, McAulay draws attention to Keith Sanger’s work on Daniel Dow’s Collection of Ancient Scots Music and the interest it drew from those interested in curating a distinctive ‘Highland’ music (p.191). Robert Petrie, a composer and collector of dance tunes whose subscription base seems to have been mostly male, also received some consideration, as later collections seem to have had more overtly ‘Gaelic’ material, supported by Gaelic speakers from Perthshire: Petrie himself played in Perth balls, and this shows how particular locations impacted on what a composer might want to be able to publish (p.193).

Both these chapters are satisfyingly based on deep engagement with solid data, and both reinforce the other’s findings. Together they present a fascinating portrait of a period of transformation, from an older society of patronage-driven culture, and a newer one of liberal market economics, where both men and women had distinctive roles to play in a growing musical business sector.

Further Reading

- Simon D I Fleming, Martin Perkins, Music by Subscription: Composers and their Networks in the British Music-Publishing Trade, 1676-1820 (London: Routledge, 2021) – particularly chapters by Simon Fleming on Edinburgh women’s presence in subscription lists, and by Karen McAulay on subscription and dance tunes.

- Keith Sanger, ‘General Reid and Daniel Dow: The Elephant in the Room’, an article on the subscription list for Daniel Dow, A Collection of Ancient Scots Music for the Violin, Harpsichord or German Flute: Never Before Printed, Consisting of Ports, Salutations, marches or Pibrachs (Edinburgh, 1778).