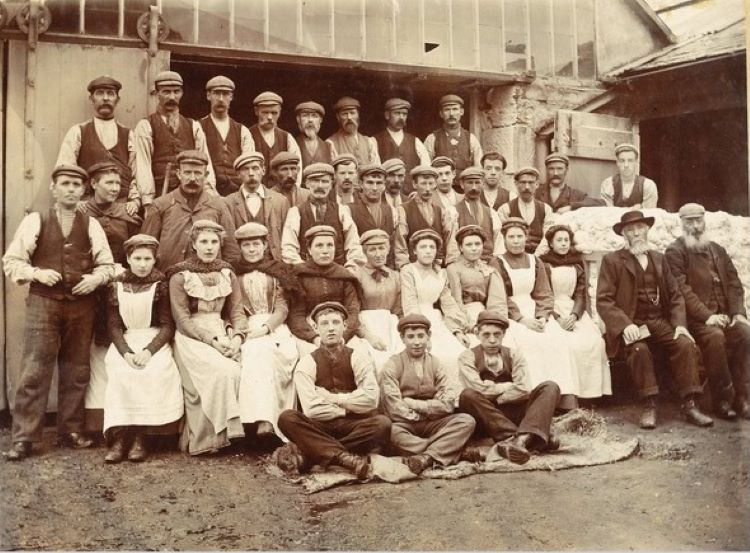

Featured image: DUNIH 353.22 Dundee linen workers, c.1865, at Cargill & Co. Bleachworks up by DIghty Burn, with thanks to Dundee Heritage Trust

During the Covid19 lockdown, the Traditional Song Forum moved its meetings online including its 2020 annual conference, which had the fortuitous side effect of helping those people in the northern part of the British Isles attend and speak at events normally located in-person south of the border. The outcome of this is volume 3 in the TSF’s series of folk song studies, Thirsty Work and Other Legacies of Folk Song, edited by Steve Roud and David Atkinson, which includes several essays by Scottish researchers. This post summarises three essays, linked by a common theme of musical travel.

The whole volume has many delights including the essay flagged in the collection title, by Katie Howson, which discusses a short series of broadcasts made from pub-located folk sessions during the second world war, to raise troop morale. But for Soundyngs purposes, we are fast-tracking to the essays specifically on Scottish topics, and find that in each case, journeys feature in ethnographic methodology and practice.

The Gaelic Homer

The territory north of the Great Glen is surveyed by Karen McAulay’s essay ‘Alexander Campbell’s Song Collecting Tour: ‘The Classic Ground of our Celtic Homer’ (pp.180 -192). This piece takes us back in time to the early years of the 19th century, 1815 to be precise, when Campbell, who taught Walter Scott about Scottish music, embarked on a music collecting tour of the Highlands and Islands using the traditional modes of transport that are feet, horse drawn coaches, and small boats.

Campbell’s tour was inspired by the earlier work by James Macpherson on Ossian, and bagpipe manuscripts by Patrick McDonald recently published in Edinburgh. Believing Macpherson’s work to be authentic, Campbell had already published on Scottish songs. Now, funded by the Royal Highland Society of Scotland, and in particular, of Sir John Macgregor Murray, Campbell followed his leads from Stirling north- and westwards, taking in Lismore, Mull, Iona, North and South Uist, Barra, Vatersay, Harris, Skye and then back onto the mainland. On the way, he spent time with tradition bearers – bards, bagpipers, work songs, harp airs and more – transcribing the melodies he heard into conventional scores and taking time to sing it back to the performer (p.186) to check it was ‘right’. Another tour, to the Scottish borders, in 1816 extended the finds.

Once back in his study, Campbell added – inevitably – suggested harmonies in the contemporary classical style, and this hybridised material in a short time appeared as the 2-volume Albyn’s Anthology (1815 and 1816). McAulay’s observation is that the printed material in these collections have accompaniments that are both inauthentic and at times less than entirely musically competent (p.188), and wonders if his claims to having learnt music theory from the likes of Tenducci were perhaps exaggerated. Nevertheless, ‘from a musical point of view, the tunes make good source material, and musicians nowadays make their own settings of them, discarding Campbell’s harmonies’ (p.192).

Railway Strikes, Industrial Ballads, and Folk Song

Sometimes it is the songs rather than the ethnomusicologist that embark on journeys. In a summer marked by strikes in British rail transport, it is interesting to read about similar periods of industrial unrest in Colin Barger’s article ‘Railwaymen’s Charity Concerts, 1888-89’ (Thirsty Work, p.97- 111) Covering ballads written to highlight the cause of worker discontent and concerts held to raise funds for the families of strikers and families, material surveyed in this piece covers all corners where the railways reached, which in Scotland includes events in Glasgow and Wigton, although not north of the Great Glen. Ballads written to draw attention to the railworkers’ discontents were reviewed in contemporary publications such as Songs of the Rail (1878) and The Railway Review (1888 and 1889). Along with songs, the idea of workers’ benefit concerts travelled all over the country, following the railway lines, wherever common cause could be found. Community-organised benefit concert programmes included, overwhelmingly, songs, but also instrumental pieces, spoken recitations and readings, sketches, dance and other acts. Of the songs, many were popular music hall items (Thirsty Work, p.106), but about a third of the songs seem to have been folk songs. Only a few items would have been the topical ballads – but perhaps these would be all the more effective for being placed within this accessible, familiar kind of variety entertainment.

It would be interesting to find out more about whether the folk songs in different cases reflected just the regional placement of the concerts, or else were a kind of generic British ‘folk song’ whose dispersal nationally was aided by greater national transport integration afforded by the railways. What is clear is that one or two new ballads relevant to the occasion, such as ‘The Iron Horse’, cropped up in several locations (Thirsty Work, p.109).

Tayside Flax-fields

The final essay in this volume discussed in this post is by folklorist and singer Margaret Bennett, whose recent research into the work of William Montgomerie brings her to another Scottish repertoire: ballads sung by rural workers as they travelled, by horse and cart, between rural flax fields to the mills Dundee, then back out to the rural bleach fields, and finally back again to the city. In ‘William Montgomerie’s Fieldwork recordings of Scottish Farmworkers’ (Thirsty Work, pp.193 –209). Bennett provides a biography of Montgomerie that explains both his background education and training, and his meticulous fieldwork method.

By the time Montgomerie was recording these songs in the 1950s, the actual practices described were historic: the Dundee mills were closing or closed, and he was recording elderly men in their 80s who remembered the songs of their youth (p.197). These are a particular sub-type of the ‘bothy ballads’ of the rural NE of Scotland, sung not only in ‘bothies’ by young men, but also in families by these men when they later married, and eventually, in their old age, as reminiscences of lost times. Songs from singers like William Milne recall stories about farm life, hiring fairs and love – and not just of women, of horses. William Taylor’s song about the ‘Panmure Bleachfield’ (Panmure is east of Dundee) is particularly vivid (p.201), describing two contrasting cart horses and what life was like sitting on a cart pulled by these great beasts. Bennett provides a vivid reimagining, interlacing ethnographies with song lyrics, of what this local flax economy was like before the work moved overseas. Further north, and circling back to the railways, we hear of Bert Coull’s rendering of a fishwife’s song about travelling on the trains and chatting to folk she met in her travels: ‘Don’t Let Us Be Strangers’ finds its way into broadside printing (p.203).

Conclusion

What these 3 essays show is that attention to the travel-paths of folk song – by foot, cart and rail – sheds light on the transmission of repertoires not only locally but inter-regionally. In different ways, these songs show how modern patterns of mobility have contributed both the creation and preservation of this material.

Further Reading and Resources

- Steve Roud and David Atkinson (eds.), Thirsty Work and Other Legacies of Folk Song, (London: The Ballad Partners, 2022) in which –

- Colin Bargery, ‘Railwaymen’s Charity Concerts, 1888-89’, pp.97-111

- Margaret Bennett, ‘”Don’t’ Let Us Be Strangers:” William Montgomerie’s Fieldwork Recordings of Scottish Farmworkers, 1952, pp.193-209

- Karen E McAulay, ‘Alexander Campbell’s Song Collecting Tour: “The Classic Ground of our Celtic Homer”’, pp.180-192

- The Traditional Song Forum